|

Poetry & Sculpture: David Cope and the Making of

Two Poems:

"A Dream of Jerusalem"

and "I, You, She, or He"

By David

Cope

|

|

|

|

Frederik

Meijer Gardens

Sculpture Park

Poetry & Sculpture: Poetry based on the works of Jauma Plensa

brochure, 2008.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction

|

|

|

|

Michigan poet David Cope was invited to

read two poems, "A Dream of Jerusalem" and "I, You, She, or

He," inspired by the work of Jaume Plensa (Spanish, 1955) at the Frederik Meijer

Gardens of Grand Rapids on November 7, 2008. The Museum of American Poetics,

in collaboration with the Meijer

Gardens, invited Mr.

Cope to comment on the process involved in the making of the two poems for

this sculpture-poetry event. Michigan poet David Cope was invited to

read two poems, "A Dream of Jerusalem" and "I, You, She, or

He," inspired by the work of Jaume Plensa (Spanish, 1955) at the Frederik Meijer

Gardens of Grand Rapids on November 7, 2008. The Museum of American Poetics,

in collaboration with the Meijer

Gardens, invited Mr.

Cope to comment on the process involved in the making of the two poems for

this sculpture-poetry event.

|

|

|

|

About Jaume Plensa

|

|

|

|

Jaume

Plensa was born 1955 in Barcelona,

Catalonia, Spain.

He is an internationally renowned contemporary artist and sculptor, known for

major public art projects. His outdoor work can be seen in locations

including the US, Canada, France,

Japan, Germany, Switzerland,

Italy, Korea and the UK, as well as in his home

country. Plensa is perhaps best known for Crown Fountain, a

monumental and very popular public sculpture in Millennium

Park, Chicago. While Barcelona

remains his home and base, Plensa has lived and worked in a number of other

countries, including England,

at the invitation of the Henry Moore Foundation, and France, at the

invitation of the Atelier Alexander Calder. He is the winner of various national

and international awards, including the Medaille des Chevaliers des Arts et

Lettres from France's Minister of Culture in 1993, and he has had numerous

solo exhibitions throughout Europe, North America and Japan. Jaume

Plensa was born 1955 in Barcelona,

Catalonia, Spain.

He is an internationally renowned contemporary artist and sculptor, known for

major public art projects. His outdoor work can be seen in locations

including the US, Canada, France,

Japan, Germany, Switzerland,

Italy, Korea and the UK, as well as in his home

country. Plensa is perhaps best known for Crown Fountain, a

monumental and very popular public sculpture in Millennium

Park, Chicago. While Barcelona

remains his home and base, Plensa has lived and worked in a number of other

countries, including England,

at the invitation of the Henry Moore Foundation, and France, at the

invitation of the Atelier Alexander Calder. He is the winner of various national

and international awards, including the Medaille des Chevaliers des Arts et

Lettres from France's Minister of Culture in 1993, and he has had numerous

solo exhibitions throughout Europe, North America and Japan.

|

|

|

|

A Dream of Jerusalem

|

|

|

|

by David Cope

|

|

|

if in time the city has been, will be desolate, the

scattered bones chirping in dry day,

the woman calls her lover to come away, searches without

finding, sings silently

that none may turn to Love until it descends in morning

dew and in calling doves.

as bone fragments & ashes swirl in shining waves, sink

into dark murk & are gone

one turns in dreams to the child’s eye, the dark

circles of bone where the mother’s

vision once stirred—where her cheek met the small

hand reaching thru space:

we are creatures made of words rounded by incantation

& the great lyric dream,

the fullness of young lovers sharing wine in the moonlit

night in the garden, swearing

they’ll not turn to Love until it descends in

morning dew and in calling doves.

here, in mountain air & silence before dawn, in the

spirit borne of blind sight,

cross-legged, the shofur nearby untouched—in this

heart shaped by words there is

a presence that could in a soundless tomb shiver the dark

with hammers, sound

the call in waves shimmering in all the wheels turning

across the universe & make

seraphs weep. yet there is the stillness of the word, the

child’s mind that turns to

her mother & touches her skin made of words: words

that measure breath to be

shared as tender touch in passing time: brothers cry out

at the prison door, women sigh

in their last dank beds, boys turned men shoulder rifles

behind dusty tanks & blood

is the cry thru a thousand cities. here there is silence;

here light & form where words

bring the lovers together, here the dream of soft bodies

moving together, the dream

at once the child’s cry & the mother’s

last gasp exhaled in fierce sunset as if

none may turn to Love until it descends in morning dew and

in calling doves—

here the desolate city, deserted temple, the lost tribe:

here the dream wrapped in words

that round the breath in silent air: here the ashes that

once were man, the bright dream

& endless night, here sun disc’s eternal round

in silence, unheard music of spheres:

let the woman call thru the city & on the mountain for

her lover, and if she searches

without finding, she may hear the scattered bones chirping

in the dry day & sing silently

that none may turn to Love until it descends in morning

dew and in calling doves.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

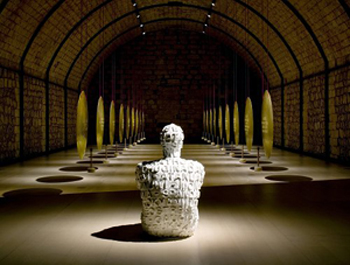

Jaume Plensa. Jerusalem, 2006. Bronze, rope, wood

and wool, 18 gongs, 52 inches diameter each.

Courtesy of Jaume Plensa, Jerusalem.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"A Dream of Jerusalem" begins with my own

associations with the city through William Blake's prophetic

"Jerusalem"—the city itself as a metaphor for imaginative

redemption—and through childhood reflection on Jerusalem as locus for

both spiritual journey and holocaust, the latter including the Lamentations—the

fall of the city, destruction of the temple, and the Babylonian

captivity—as well as the slaughter of the population and destruction of

the second temple c. 70 CE. as recounted by Josephus in The Jewish War.

There were also countervailing associations: Plensa's inscription of lines

from the Song of Songs on the two parallel rows of giant gongs which

with their sounding hammers form the sculpture. Song of Songs is a

woman's book, a book of love and longing, and of the spiritual sexuality of

love itself, and in thinking about the poem I would write, I recalled the

woman's search and the famous refrain in 2:7, 3:5, and 8:4, which I rendered

freely as "none may turn to Love until it descends in morning dew and in

calling doves."

While this line would become the refrain for the poem, I did not begin by

thinking of it as such; in the initial composition, the line repeated itself

in the 9th line-it just seemed to fit there—and it came up again as the

final line of the poem. Later, I reworked a lot of the lines in the middle

sections, largely for condensation of phrasing and for specificity of image,

and in this process repeated the line as the 21st line, thus framing the poem

up with two refrains at the beginning (lines 3 and 9) and two at the end

(lines 21 and 27).

This was immensely satisfying for me, as I have long been fascinated with

weaving and the construction of tercet and couplet-based

poems—variations on the dantescan and ghazal patterns of

construction—as a kind of weaving. "A Dream of Jerusalem"

became a kind of Mexican blanket for me, with the refrains as stripes

repeating each other at each end of the blanket.

Beyond the pattern, I was fascinated by Plensa's sound hammers and his request

that those experiencing the work should take up a hammer and hit the gong

nearby. More fascinating for me was the potential for sound and the notion of

sound or action moving out in waves which imply changes far beyond the

initial action, as in Basho's famous "frog kerplunk" poem. I myself

had explored this concept in my 1993 poem "Catching Nothing" (Coming

Home 102-105), which ends with this idea of action changing the world:

even

our hearts beat like

hammers now, sending out waves of sound

over & over—

the breath

is a wind that

stirs up all the world.

When I came to Plensa's notion of the gongs, this binary

concept of stillness/action found its form in the idea of the shofur

untouched and of the "presence that could in a soundless tomb shiver the

dark with hammers, sound the call in waves shimmering in all the wheels

turning across the universe & make seraphs weep." Silence thus

became the meditative center of the poem, a priori the "unheard music of

spheres" which cannot be heard in a fallen age.

The last major association was the idea of the woman herself-in Song of

Songs, fairly obviously a young woman in the prime of her

youth—yet I also thought of her as the elder she would finally become,

of Time itself. I had lost my own mother this year, thus the importance of

the child reaching out to touch the mother's cheek, the bone where the

mother's vision once stirred, and finally the ashes which "swirl in

shining waves, sink into dark murk & are gone"—an image from

the final ceremony after my mother's death, wherein my siblings cast my

mother's ashes into the river where she raised us. The poem is thus the

central poem in that sequence of works exploring my mother's passage from this

life and my own self-discovery borne of that passage.

In the associations which come with my mother's passing, there is also the

image of the "scattered bones chirping in dry day"—that

astounding image from the valley of dry bones in Ezekiel, wherein

the voice asks the prophet whether these bones shall live (Ezekiel

37:3). The part of my mind that was revolving on the associations with my

mother's death picked up on the chirping bones, an image I had previously

combined with the notion of Christ as "the word made flesh,"

turning the phrases in my 1993 poem "For Martin

King"—"who sang the flesh made word that bones may

walk." The image returned here as a rebirth, as the city itself has been

reborn.

All these associations were activated when I first encountered Plensa's Jerusalem; when it came

to the composition, the words came quickly. It was as if I already knew them,

and of course it had nothing to do with the ridiculous notion of occasional

composition, but rather with opening oneself to the associations

evoked by the work. The work quite naturally fell into the pattern of

long-lined tercets, a format I have been very comfortable with ever since my

extensive interrogation of Dante's Commedia. Some minor motifs

popped up in the fury of the writing—the notion of "blind sight,"

borne of my years of watching Olivier's film of King Lear every

Sunday morning and borrowed from my 1990 poem "Vision"—as

well as the Egyptian idea of the "sun disc's eternal round" and the

aforementioned medieval concept of the music of the spheres. The images of

the world in crisis, whether brothers crying at the prison door, the women in

the "last dank beds," or boys shouldering rifles behind dusty

tanks" are generic images from the news, yet they are also specific,

minute particulars which identify actual events.

The composition itself involved centering oneself in a consciousness which is

ultimately receptive to all the images that derive from the above

associations. The harder part was in revising it so that it would achieve the

form it now has. The poem went through three such revisions.

|

|

~~~~~

|

|

three dreamers sit together on green, grown

yet coyly clasping hands below knees—

facing each other like lovers, emergent as

hollow, their flesh & form become shining

letters in patterns where once words became

lines by which they measured lives, words

which became them. manitou winds blow

softly thru leaves, thru vacant heads & torsos,

lips still forming sighs lost forever—they

might have danced in starlit nights or sang

heartsongs for lost love, as if they live still

in a dream now lost to a generation racing to

its own dead ends. Now there is silence

on the green where a distant child’s echoing

song is lost in one horizon-bound jet trail,

where the dreamers sit in stasis: we three

too have come to look at them, animated

in our conversation, lost already in dreams

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

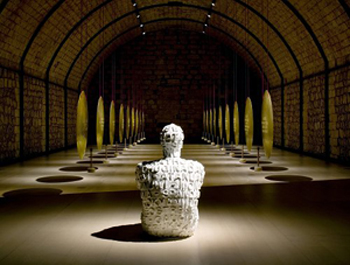

Jaume Plensa. I, you, she or he...

(detail), 2006, stainless steel and stone.

102 x 71 x 106 inches, 105 x 73 x 102 inches, 102 x 66 x 78 inches (including

stone).

Collection of Frederik Meijer Gardens &

Sculpture Park,

Gift of Fred and Lena Meijer.

|

|

|

The title of "I, You, She or He" fascinated me

before I ever saw the installation firsthand; I had seen the photos of

it—three seated figures almost like "The Thinker" in their

individual poses, yet a grouping which suggested a shared dream. The title

suggested the indeterminacy or fluidity of identity, as in the central

concepts of queer theory or in John Lennon's famous line "I am he as you

are he as you are me and we are all together." I was also

continuing my meditation on Plensa's use of words or alphabet letters as

flesh, skin, or form, the idea that our words are/become our flesh, our

demarcating limits, our form.

The process begins with a walk out to see the installation at Meijer Gardens. Poet Linda Nemec Foster

and I had met with the Gardens' contact person, Heidi Holst, to talk about

the Plensa exhibition and our part in it, and the three of us then walked out

to see "I, You, She or He." We had also talked of the much

larger installation, "Nomade," which is similar in form but large

enough so that the spectator can walk right inside the piece and thus

"become its spirit." This brought all kinds of associations

with Dali and the surrealists, the philosophical notion of the "ghost in

the machine," and I sort of ran with that when it came to the poem

itself.

The poem begins with a simple description of the sculpture as seen on the

bright summer day when we were there, and in composition the hollowness of

the pieces and the "shining letters in patterns" led to "the

lines by which they measured lives." I moved from that to images

of the lives they led, the loves and gestures which defined them now reduced

to memory or conjecture and the fact that the current generation is still

"racing to its own dead ends," a pun which I couldn't resist.

Returning to the scene at hand, I heard the calls of children over the green

and thought briefly of the "ecchoing song" of Blake, at the same

time noting the jet trail above. The poem ends with the peculiarity

that here we were, three of us, observing these three sculptures, our own

lives bending inexorably toward the dream embodied in the works before

us. It was pretty simple to write: partial association, partial

direct observation, and once again, opening oneself to the energy

embodied in another's work.

|

|

|

|

Notes on the Texts (bibliography of ekphrasis in

literature, provided by the poet)

|

|

|

Ekphrasis as a Literary Device: Three Periods

Ekphrasis, or the detailed description of a work of art as emblematic of the larger

themes or as the entire focus of a poem, has a long and distinguished

history. Some examples:

Some Ancient and Medieval Examples

Homer, the shield of Achilles in Iliad, book 18.

Virgil, Aeneid VI: 28-46, carvings of Daedalus on the Temple of Apollo

- - - - , Aeneid VIII: 810-955, shield of Aeneas, with

the founding of Rome

and the

apotheosis of Augustus.

Ovid. Metamorphoses 2.1-18 The palace of the sun.

Catullus, "The Marriage of Peleus and Thetis," #64, lines 48-259,

the ornamental

bedspread and covering of the marriage bed, which tells the story of

Ariadne.

Dante, Purgatorio X: 109-110, the Cornice of Pride

Chaucer, The Knight's Tale, Pars Tercia: building of the amphitheatre,

description of the temples

Renaissance through the Romantics

Ben Jonson. "To Penshurst."

John Milton. Paradise

Lost, Book 1. Pandaemonium.

John Keats. "Ode on a Grecian Urn."

Some Contemporary and 20th Century Examples

William Carlos Williams. WCW's relationships with painters (especially

Hartley and Demuth) is pretty extensively documented, and even in poems that

don't specifically refer to painting or art, he often frames them up as in

ecphrasis. Examples abound: "Portrait of a Lady,"

"A Portrait of the Times," "The Botticellian Trees,"

"Proletarian Portrait," "Portrait of a Woman in Bed,"

"Sympathetic Portrait of a Child," "A Portrait in Greys,"

"Portrait of the Author," "Perpetuum Mobile: The

City," "The Three Graces," etc. Many of his poems do

respond to specific pieces of art:

- - - - , "The Great Figure" This famous poem is a response

to Charles Demuth's painting, "I Saw the Figure Five in Gold"

- - - - ,"The Dance" ("In Breughel's great picture, The

Kermess. . . ")

- - - - , "Picture of a Nude in a Machine Shop." (anonymous

calendar art)

- - - - , "The Birth of Venus" (ref. to Botticelli and others)

- - - - , "Pictures from Breughel" (Self-Portrait, Landscape with

the Fall of Icarus, The Hunters in the Snow, The Adoration of the Kings,

Peasant Wedding, Haymaking, The Corn Harvest, The Wedding Dance in the Open

Air, The Parable of the Blind, Children's Games)

W. H. Auden, "The Shield of Achilles."

- - - -, "Musee des Beaux Arts."

The Poets.org link below can give one many other examples in 19th and 20th

century poetry.

Some Resources

Definition at Online Encylcopedia: http://www.encyclo.co.uk/define/ecphrasis

Ecphrasis: poetry confronting art: http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/5918

Ecphrasis: "Hollander answers": http://www.d.umn.edu/~jjacobs1/utpictura/1.htm

Ecphrasis in Russian and French Poetry: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3763/is_200209/ai_n9096904

"Ekphrasis." The New Princeton

Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Ed. Alex Preminger and

T. V. F. Brogan. Princeton: Princeton

U P, 1993.

Laird, Andrew. "Sounding Out Ecphrasis: Art and Text in

Catullus 64." The Journal of

Roman Studies 83 (1993): 18-30.

Quinn, Kelly A. "Ecphrasis and Reading Practices in Elizabethan

Narrative Verse." Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 44

(2004).

|

|

|

Jaume

Plensa was born 1955 in

Jaume

Plensa was born 1955 in