KRISTIN PREVALLET

NAVIGATING THE NEW CHAOS:

ANNE WALDMAN’S COLLABORATIONS WITH VISUAL ARTISTS

The convergence of poetry and visual art begins with a meeting of minds.

Consider Anne Waldman: her exploratory poetic projects reinvent, rearticulate, refathom, redraw, and reconstruct as a means of

interpreting the world around her. Collaboration with artists is yet another

means to find, as Waldman writes, “a kind of go-between between states of mind

hidden (heart, body) and states of mind realized/enacted as well as

what’s overheard” (Vow, 269; emphasis in original). Looking at visual

art provides an interesting challenge for exploratory, oppositional, Kali Yuga,

anti-genre poets. Finding forms in the world that illuminate the complex states

of our human reality, the poet’s words explode off the page into new forms.

Thesis:

Q: How can we now navigate a new chaos of possibility?

AW: Study “how art stretches the boundaries of logic” (Vow, 128).

Q: Or: Stretch boundaries of logic and navigate chaos!

Waldman’s collaborations manifest concepts of multilayered intelligence in a

different way than her textual work where the palimpsest of lateral thinking

reveals itself between genres and shifting modes of articulation. Her work with

visual artists reveals less what she knows in a practical sense and gets more

to the thinking behind the creative process. In Waldman’s work, no

matter how many multiple worlds are engaged, she actually manages to live, to

be local, in each one. The only exception to the work she does with artists is

that the lived space is more explicitly a shared one.

One way to stretch logic: imagine a space, and then fill it. Waldman writes:

“To conjure a particular knowledge you visualize an architectural structure and

then you walk around and see the details that then bring back the words or the

poetry or the line of thought” (Vow, 286). This concept of the

architectural imagination is useful for discussing how an artist and a poet get

together and collaborate. Visual art — an Yves Klein azure abstract canvas or

an intricate Jess collage — enable writers to imagine a space. Once the writer

can see something in the artwork reflected back into her own mind, the

collaboration has begun. This activity of looking through a work of art

involves a certain level of self-reflective thinking. Meaning that what you

write in relation to a work of art is going to be different from anything you

have written before.

Mental Illustration #1

There is a story from the Bhagavata Purana about a little boy named Krsna

who had a mind of his own. He herds the animals at the wrong time of day; he

laughs when people are angry and shouting at each other. He thinks food is

sweet only if he steals it, and he distributes his food to the monkeys. One

day, the other children tattle on him: they tell his mother Ysoda

that Krsna has eaten dirt. Krsna

denies it, and opens his mouth to prove his innocence. However, it is not Krsna who is opening his mouth, but a god, Hari, who has taken the form of the child. When Ysoda looks into his mouth, she sees everything: the

regions of the sky, the earth with its mountains, islands, and oceans, the

wind, the lightning, the moon and stars, the zodiac, and space itself. She sees

the vacillating senses, the mind, the elements, and the three strands of

matter. Seeing all this, she begins to question herself. She wonders, is this a

delusion of my own perception? She sees that her entire world is constructed

with false beliefs. She questions her ego, and she suddenly sees herself as one

among a series of cosmic particulars. What she sees, in other words, is herself

in the context of all that is simultaneously happening around her — her

individual self is contextualized within multiplicity, within something much

larger than herself.

Of course, the Bhagavata Purana

is a sacred text, and so the image gyrating in the boy’s mouth was a divine

gift — but as Blake evidenced, there is a fine line between divinity and

imagination. The mother Ysoda, a poet in her own

right, looked into a space and then filled it with the vastness of her mind. In

doing this she altered the boundaries of herself in relation to the world.

Thesis:

AW: “I write to make up a world, it’s true. I live inside that ‘world’ or

universe. You’re welcome to come in as well” (Vow, 131).

Q: But how can I see into your world and make sense of it?

AW: “The poet’s imaginative eye triggers the synapse creating a complete

universe, a bubble of perception which brings the vision of an infinite reality,

or construct, together with tangible detail. It’s up to you (human realm) to

make the connections” (Vow, 171).

Artist/writer collaborations — looking into created spaces and seeing a

convergence of minds — are quite ambitious. The ideal collaboration between an

artist and a writer is one in which each disappears into the synthesis of their

respective minds. When put together, these two minds become what William

Burroughs calls a “Third Mind” — the “unseen collaborator” that results in the

emergence of a new author. As Waldman explains it, “something

new, or ‘other’ emerges from the combination that would not have come about

with a solo act” (Vow, 326). This kind of collaboration is

different from a writer who writes a poem to illustrate an artwork, or an artist

who draws a figure to represent the mood of a poem. The Third Mind actually

involves the writer and the artist giving up their own particular egos and

creating something together that they never would have imagined doing on their

own. It happens when the poet and the artist see into each other’s processes

and are able to make something happen in their own process that reflects what

they see. It is a synthesis that may look disconnected, exploratory, fragmented

— or, it may take on a form that is surprisingly synthesized. Given Waldman’s

poetics, the way that her relation to lived multiplicity reflects the

complexity of the world around her, this level of ambitious collaboration comes

naturally.

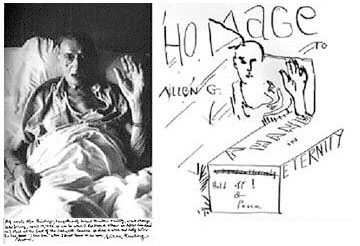

Figure 1: Homage to Allen G., with George Schneeman

This is the story of a memorial: The artist George Schneeman had conceived of a collaboration he wanted to do with Allen Ginsberg. Schneeman had traced Ginsberg’s photographs, and then wanted him to provide a text for them. Ginsberg had already written explanatory captions for his photographs, so he would in a sense be writing another kind of caption — this time, one that is a trace of a trace. Not a caption that represents the actuality of the photograph, but rather one that manifests the absence of the person that used to be in the photograph. Schneeman did not know at the time he conceived of the project that Ginsberg was dying — his cancer had not yet been diagnosed. Schneeman proposed that Waldman complete the collaboration with him as an homage to Ginsberg — and the same night that he died, she worked with Schneeman’s drawings. Collaboration in this case was like a ritual, the completion of something pending, the assurance of a full circle — a way of grieving that was about being with the person just lost to the world. In an interview with Lisa Birman about her collaborations with visual artists, Waldman says, “It was consoling to have a place to put the grief which also included the literal traces, as well, of Allen. I stayed up all night sitting in front of George’s tracings, and wrote a few lines at a time. Working with the drawings was like working with the literal traces of Allen” (Vow, 322).

Homage is an example of how text and image work together to create a

new context. The cover image of Waldman/Schneeman’s

Homage is a powerful transference of Ginsberg’s uncle Abe. Schneeman’s drawing with Waldman’s text opens the

photograph up to new levels of interpretation and meaning. In the drawing Abe

is on his deathbed, reluctantly raising his hand as if an enormous amount of

effort was put into this gesture. This same hand which was struggling to be

raised in the photograph becomes, “A hand in eternity.” The allusive yet

specific quality to the text allows the drawing to be read in a multitude of

ways: the hand is waving goodbye as the spirit enters eternity; the hand is

guarding eternity; the hand is the hand that has done so much work to shape and

create an eternity here on earth.

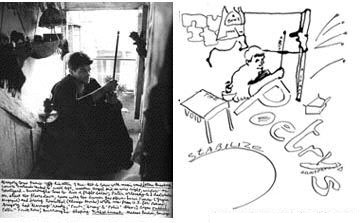

The mendicant Corso looking like a wizard on the

verge of using his magic wand to communicate some great message,

Ginsberg’s photograph enters into mythic terrain and has many possible

narratives. In the drawing, the figure retreats to the background, and

what come through are POETRY’s accoutrements: the objects necessary — a

bowl, a rod, a staff, a table — to hold up the void. Writing the text,

Waldman says that she was thinking both of “Gandhi’s possessions at the

time of his death” as well as “Allen’s particular modesty” (Vow, 322).

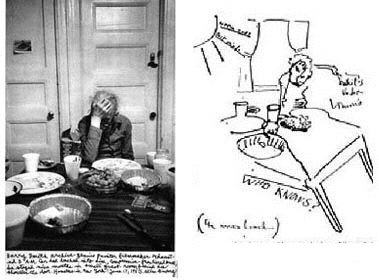

Here is Harry Smith: sad, tired, confused, and in

pain — Ginsberg’s caption tells of his story, “homeless in New York.”

Surrounded by empty plates and a bowl of grapes. In the drawing Smith

is transformed. He becomes “the thinker.” Utilizing “Best Minds” in the

text, Waldman is again finding Ginsberg. But she is also seeing Smith,

changing him from a despondent old man into an old man burdened by the

chaos of the world. What loose fragments are under his thumb? Who

knows? But in the drawing is a sign of hope that was missing in the

photograph, a sun with words on its rays. The table is filled with many

cups. In the photograph they were half empty. In the drawing, they are

the accruements of a mind that has absorbed a lifetime of information.

Mental Illustration #2

The word “Ghost” means that one person has left a place, only to be given presence, interpreted back into life by another person. Collaboration is working with ghosts in this sense — looking at something and reinterpreting it, bringing it into a new life.

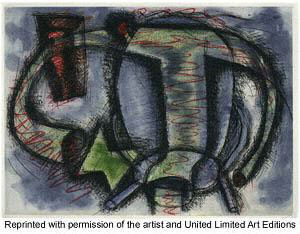

Figure 2: Kin, with Susan Rothenberg

There is an epigram at the beginning of Kin

that gives a direction on how to read it. It tells about early myths in

which animals and humans are transferable — the very idea conjures up

stories of werewolves and boys who become horses. For this to be the

case, as Waldman writes, animals and humans would have to speak the

same language.

Opening the book, the eye is drawn to Rothenberg’s

drawing in the center of the book. Flipping through, the shapes are in

the process of transforming.

Wavering between the

expressionistic, elusive, and abstract to the chatty and informal, the

poem is divided between the drawings — physically on the page, and

tonally in the language. While the images are in the process of

splitting, shifting, and transforming, the text moves along as if

propelled by its own internal energy, as if it too were undergoing

physical changes. The poem moves in and out of “sense” — it is

difficult to follow. Does the confusion of the text reflect the state

of becoming another thing? What consciousness is propelling cellular

division, nuclear mitosis, globular shape-shifting? If the two parts

are speaking to each other as they come together, what logic can they

possibly be attempting to utter?

In the final folio the poem reaches for some explanations:

could be a measure in force

could be an apocalypse

could be a shift in consciousness

could be a new language

The poem is struggling with its own voice — its language is fragmented

and what it is referring to is not specific. The text is in a state of

flux that mirrors the changing state of the drawings. And as the poems

struggle to articulate whatever transformation they are going through,

the drawings are undergoing their own process of changing into another

shape. Waldman’s Kin

is an example of how to write a poem that is not merely illustrating an

artwork, but rather is responding to it in a parallel fashion. The

language itself is enacting motion; the poems and the artwork have

synthesized to become a part of the same creative process.

Mental Illustration #3: The book is yet another mind.

If collaboration is the synthesis of multiple minds, how can this be manifest as an object? In both Homage to Allen G. and Kin, the form of the book is as important as the work contained within it. In Homage, the pages are loose — like photographs. In Kin, the book, divided in three, embodies triptych consciousness. The book provides the form and shape for the collaboration to be present in the world — it is not merely a container for the collaboration, but is itself parallel to the work. Steve Clay, the publisher of Granary books, is the third and unseen collaborator in this process. He is the man-behind-the-seen who has to imagine the space created by the collaboration before he can set to designing the book.

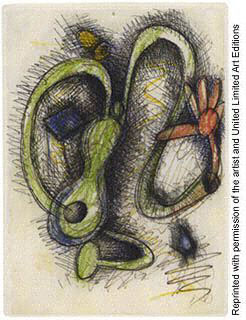

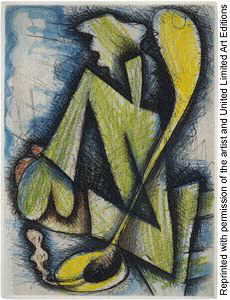

Figure 3: Her Story, with Elizabeth Murray

There are many stories about paintings. In Her Story, Murray’s drawings are cellular, mutating, nuclear, nucleus, openings around liquid matter where small intersections of shapes are floating... bodies in the process of being formed, something between animation and machine, between organic and synthetic, between anemone, monster, and human.

The act of imagining a space entails that the writer actually go in and interpret what the artist is trying to do — revealing the parts while simultaneously seeing the whole. In Her Story, Waldman looks very closely at what Murray is doing and then finds a form for it in language. She describes her reading of Murray’s work: “The drawings are coils, bursts of energy, fantastically witty, like cartoons gone awry yet made elegant in their transformation. She seems located in ‘things,’ but what are they?” (Vow, 324) Here Waldman is looking at the artwork in a particular way in order to find a point of intersection where she can find her own form in language.

A wrench is a power

instrument

getting itself

together

getting ahold

the way we are

The way a vise

keeps us in shape

I want to be a

viceless small thing

wrapped in a blanket

put me down.

The second of Murray’s drawings in the sequence has two discernible shapes that have broken away from each other — one is floating in the sky, the other is cascading across the ground — each is in its own form that makes sense where it is in space. Waldman writes, The picture is

distinguishable

from me

the model

Lines are drawn by feeling

the feeling

will no longer

help you draw

on your past

Forget it

my arms are

hollow tubes

you aren’t there

anymore.

She has wrestled the tubular amoebas and has found her way through the tangle of primal mess — those strings and quarks that keep it all together. Seeing herself in the context of a larger world, Waldman looks into Murray’s drawings and sees an individual body being held together by a larger, unstructured universe.

Figure 4: No Hassles: An Unhinged Book in Parts

Writing about alternate logics and parallel universes is a particular

kind of reading into artist collaborations that neglects one very

important element — fun! People coming together with their particular

minds to get into each other’s heads. People working to collectively

discover shapes and forms that haven’t yet been named. Or have been

named, but need a new name. People making poetry and art together,

because they like each other’s company and are having fun. People

hanging out at dinner parties, beach houses, and front stoops.

In the 1960s and 1970s Waldman did several different kinds of collaborations with the artists and writers with whom she was friends. The book No Hassles collects poems, cartoons, stories and photographs that document these activities. The project “Weekend,” for example, was composed in the fall of 1968 with Lewis Warsh, Bill Berkson, Kenward Elmslie and Joe Brainard — all of whom were hanging out for the weekend at Elmslie’s beach house in Long Island. The collaborations Waldman did with the poets and artists of the New York School take on a very different tone from those done later with Murray and Rothenberg. Spontaneous and informal, “Weekend” is an example of a work that is located in a particular place and time. What is emphasized are the everyday activities these creative friends do together, what they think about (their simultaneous profound and silly thoughts) at a particular moment in time.

“Weekend” is a portfolio of many different spontaneous line drawings with words floating around them. There is a very private feeling to this collaboration, as if it wasn’t conceived or composed for the outside world to read.

In the spontaneous poem “Strands,” fragments of an overheard conversation make their way into the poem, interrupting the poet’s train of thought:

S from chaos “I don’t

T hair grain life see anything

R Anne pen match here”

A Shell T.V. cup

N white sand abstraction

D “Are you doing the dishes, Joe?”

S What you see here is a

world where everything

makes sense and we

all run barefoot thru

air, like dogs.

A list to liven things

up. So great to

your eyes, so

fine.

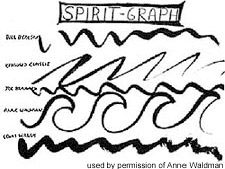

This poem, “Spirit Graph” forms a series of “signatures” as friends are asked to draw a line representing the form of their spirit:

Final Mental Illustration

Begin the process of collaboration: become a part of a larger mind, and from there, set about re-imagining your world. Waldman’s collaborations cited

Waldman’s collaborations cited

Her Story. Islet, NY: Universal Limited Art Editions, 1999.

No Hassles: An Unhinged Book in Parts. New York: Kulchur Foundation, 1971.

Homage to Allen G. New York: Granary Books, 1997.

Kin. New York: Granary Books, 1997.

Works cited

Hindu Myths: A Sourcebook Translated from the Sanskrit. New York: Penguin Books, 1975.

Waldman, Anne. Vow to Poetry: Essays, Interviews and Manifestos. Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 2001.

Works cited as figures

Figure 1: Homage to Allen G., with George Schneeman (Granary Books, 1997)

Figure 2: Kin, with Susan Rothenberg (Granary Books, 1997)

Figure 3: Her Story, with Elizabeth Murray (Universal Limited Art Editions, 1990)

Figure 4: No Hassles: An Unhinged Book in Parts (Kulchur Foundation, 1971)

[Kristin Prevallet, along with Anne Waldman, Alan Gilbert, and Bob Holman, is a co-founder of the Study Abroad on the Bowery Program at http://www.boweryartsandscience.org/. She is the author of Scratch Sides: Poetry, Documentation and Image-text Projects and the recipient of a 2003 PEN Translation Award for her translation of Sony Labou Tansi’s uncollected writings. This material is copyright © Kristin Prevallet and Jacket magazine 2005. Original publication of this essay is at http://jacketmagazine.com/27/w-prev.html. Permission to reprint was granted by Kristin Prevallet.]