BOB ROSENTHAL

ALLEN GINSBERG, REVISITED BY HIS RIGHT-HAND MAN

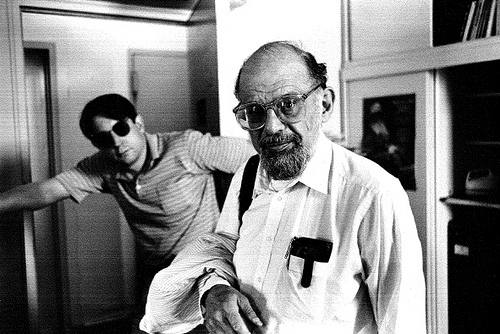

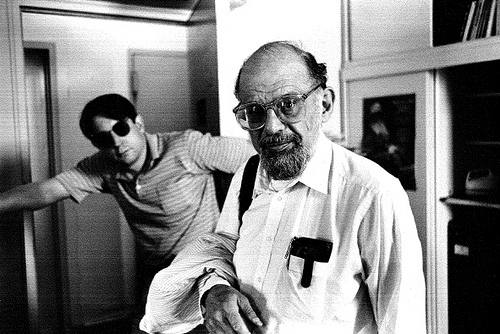

Bob Rosenthal and Allen Ginsberg. Photo by Brian Graham.

With just a few days left of National Poetry Month and a movie about the Beats in the works, it seems an appropriate time for Bob Rosenthal, former secretary to Allen Ginsberg, to share some memories of his former employer. After all, Mr. Rosenthal, an East Villager and a poet in his own right, recently completed a memoir titled “Straight Around Allen” (it’s being shopped to publishers) and he appears in “Passing Stranger,” a recently released audio tour of the neighborhood’s poetic landmarks.

It just so happens that the editor of The Local lives in Allen Ginsberg’s former apartment on East 12th Street – or rather, the portion of the apartment that contained the poet’s bedroom, bathtub, and the home office where Mr. Rosenthal worked alongside the literary legend for nearly two decades. Yesterday, Mr. Rosenthal, who these days teaches Beat literature to high schoolers, paid his first visit to his old workplace in some years, and spoke candidly about his time there.

Bob Moves to 437 East 12th, Allen Follows

My wife and I moved to New York from Chicago in 1973. We were living on St. Marks Place and met people in this building [437 East 12th Street]: Rebecca Wright, a poetess who was actually living with John Godfrey upstairs, was going back to somewhere in the Midwest where she’s from with her son and she was leaving me the apartment. It was like $125 per month and she said, “I’ll leave you these books” – all of them Allen Ginsberg books. She said, “I don’t need them anymore.” That’s when I started reading him. It was serendipitous.

My wife was working at the Poetry Project – she was a secretary. Allen, who was living on 10th Street at the time, called and he needed somebody to type a document for him, and it turned out to be a habeas corpus for Timothy Leary, who was lost in the California penal system. And when we saw what it was, Shelley typed it and we didn’t charge anything. And Allen came over here and said, “By the way, we’re looking for an apartment.” We knew the Brugalettas were leaving and said, “Oh, there’s an apartment upstairs, but don’t tell the landlady, Mrs. Seeliger, that it was us because she hates us and we’re part of the tenant’s organization.” And Peter and Allen came over and charmed Mrs. Seeliger, and got this double apartment for $160 a month.

It’s interesting – he got out of that apartment on 10th Street because he didn’t want to buy it – it was probably ridiculously cheap.

In 1977, I moved to 11th Street. I never lived in this building and worked for him at the same time, because that would’ve been too much; he would’ve knocked on the door at 3 a.m.

Bob Starts Work

I started working for Allen in ’77. When I started here, I was temporary. Ted Berrigan was my mentor and lived on St. Marks Place. Allen called Ted and said, “I need a temporary secretary,” and Ted recommended me.

I was not a big Beat fan – even then, I was a New York school of poetry fan: James Schuyler was my hero, Frank O’Hara and Ashbery and Kenneth Koch. I had read Ginsberg and thought it was really good but I wasn’t aspiring to be in the Beat world. But Allen liked me and he liked that as a fellow poet I was a little bit more upbeat. I was friendlier than the [William] Burroughs people, I was a little less suspicious – I was a little bit more like Allen in that way. He liked the way I talked to people. Very quickly he gave me financial equality – I could write his checks; he gave me a letter to give to the head of special collections at Columbia so I had full access to the stacks.

Allen’s Daily Routine

When I started, I would come in the late morning and pick up the mail at Stuyvesant Station and bring it here and sort through it and he would be getting up in the early afternoon. He’d do a little sitting meditation; he’d be reading The New York Times, sort of puttering around in his underwear. He really wouldn’t become fully charged and awake till about 5 p.m., usually around the time I sort of wanted to go. Around 7 p.m., he was really awake. But we’d work in the afternoon and I’d be taking the phone calls and things would be coming in.

I didn’t socialize much with Allen. When I first started working with him my wife was pregnant, so I had a baby really soon and I was turning 28. He would go out, meet people, usually have a late dinner at the Kiev around 1 a.m. or 2 a.m., go by the Gem Spa, pick up The New York Times, come home, read The New York Times, write in his journal; writing poems or journal entries till about 5 a.m. or 6 a.m. By sunrise he’d probably be getting a little sleepy. He didn’t sleep that much. And he’d start that whole process again. At night, he was probably mainly reading Buddhist texts. He had pretty much done the major literary reading. He had an incredible backlog of memorized poems; he could recite Wordsworth and lots of other poetry.

Allen’s Reading

In his bathroom were political magazines – Spy vs. Spy, COINTELPRO, kind of radical politics magazines: the magazine that Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting puts out, War Resisters League newsletter, I.F. Stone’s Weekly. That was the bathroom reading. He had bookshelves in the bedroom, too, containing most of his friends – that’s where he had Kerouac and Burroughs and people like Philip Whalen. He really wasn’t that adventurous in his reading. He didn’t read novels, he didn’t read plays, but he kept up. Around his bed, a lot of poetry magazines were piled up. He probably couldn’t get to them all. He liked August Kleinzahler: he didn’t always like just the known poets. He championed some lesser known poets.

The Phones

The phones here were always ringing. In “Reality Sandwiches,” one of his poems is “I Am a Victim of Telephone.” His number wasn’t listed, but it was 777-6786; it was so easy to remember. When lunatics broke out of their straightjackets they’d run to the payphone and call, and I took a lot of those kinds of calls. That was one of my jobs.

The phone calls were always interesting: Carl Solomon being a walking messenger, and kind of crazy and calling on every corner saying, “Allen ruined my life! He ruined my life!” and then: “Aw, it’s okay.” He would just be vacillating. We recorded these things – kind of crudely. We just had a cassette recorder and a cassette answering machine and I also had a little suction cup recorder. But if they left messages, I would just play it and open-air record it on the cassette. So at Stanford [home to Ginsberg's papers] there are a bunch of those cassette tapes full of messages – Gregory Corso and Carl, all sorts of people. Everything was documented. Allen had recorded a phone call he had with Kerouac – it was the only Kerouac thing he recorded – on reel-to-reel tape. We could never find that tape. It was like the lost tape.

When Allen quit smoking, he was terrible. And he quit smoking a lot. He was like a little kid: “Where’s my glue?”, “Where’s my pencils?”, “Why wasn’t this done?” He would have temper tantrums, but that was it: he’d just flail his arms for a little while. And so I would answer the phone and they would say, “Is Allen there?”, and I’d say, “Gee, who’s calling? I’ll see if I can go find him.” Meanwhile he’d be sitting next to me, and he would immediately start saying, “Tell them I’m quitting smoking! It’s a genuine disease! It’s a real syndrome!” And then I’d say, “Allen’s indisposed right now…”

The Mail

Getting the mail was a big thing. The most memorable piece of mail was a certified letter, a manila package, from John Clellon Holmes. When I opened it up, it was the first manuscript of “Howl” that had ended up in John’s hands. I looked at it and I didn’t recognize it because it was in William Carlos Williams triadic lines, but it didn’t take me long to realize what I was holding. That was very exciting. That was a centerpiece of our sale to Stanford, too.

There were a lot of weird fan letters too – a lot of ladies writing “I can cure you of this homosexuality if you let me.” Allen said, “Only my brother and my mother are Personal.” Friends would write “Allen only,” “Allen’s eyes only,” “Personal.” It was only Eugene and [step-mother] Edith who got that treatment. Everything else, I would slice them open, lay them out, get them out of the envelopes.

Allen saved the junk mail. We sorted the mail into Business, Personal, Literary, and Junk. Then we’d hire a poet to come over and go through the junk mail and write a poem about it, but actually looking for any mistakes like some good letter that had dropped in there by accident. About four or five of the poets around here wrote junk mail poems. Ted Berrigan, on his death bed, was working on a junk mail sonnet. The whole idea of taking three shopping bags full of Allen’s junk mail and turning it into a sonnet is great. Allen’s model that he learned in India was the cottage industry: he wanted to hire poets; he wanted poets to survive. So, soon I had an assistant, and I had two assistants and they were cataloging tapes. One of the rules was that every reading Allen gave should be audiotaped. Not well audiotaped – just some cassette deck thrown on the stage. Those tapes would come in and not even be listened to – they’d be cataloged and put away, and copies of catalogs were made and retyped. Allen was really into filing and retrieval, so he loved having secretaries.

We’d do all the social actions – writing letters to the governor, writing to organizations, foreign heads. I learned how to write an Allen Ginsberg letter using Buddhist buzzwords: mindful, grounded… I was getting pretty good and he would sign them and that made me feel good because he would get answers. It made more sense for me to help him write letters than for me to write letters.

The mail was huge – he would come in from being out on a reading trip or something and I’d have a stack of mail to read and I’d prioritize it from important to least important. People sent him what we’d call the Mad letters – that was another category. Those would be the single-spaced handwritten letters – six pages, 12 sides – and he would turn the pile over and he would read those first and he would spend hours pouring over these Mad letters and he would proudly show me, “Look, it makes sense! First it says this and then it says that, and then it goes there.” And I would say, “Great, Allen. Well, do you want me to answer?” And he’d say, “Oh no, don’t answer! They’ll write again!” But because there was madness in his family it was a faculty he had. He would have been a phenomenal lawyer – he was the best contract reader I ever met, and a great negotiator and great mediator between people. Thank God he was poet instead, but he had tremendous skills.

Office Music

When he was young, Allen had a lot of classical records, Indian records, a lot of blues. He loved Ma Rainey. Ma Rainey was his musical hero and after that maybe Bob Dylan. We played Ma Rainey when he was dying. It seemed like the right thing to play. In early pictures of him in San Francisco you see his room and you can see he has Bach’s “Mass in B Minor” – he was listening to classical music. But he didn’t come in and put music on – in fact, he would listen to AM 880 while he was shaving or grooming himself. He just liked to hear a little bit of the news all the time, like some people might have CNN on all the time.

Allen’s Finances

Allen hated accumulating money – he didn’t have savings accounts; whenever he needed money, he just made more money. But he had a wonderful facility for making money. He could go out for readings, he could sign photographs, he could publish books, he could do talks – anything. He was very generous. He lived a life of poverty but he made a lot of money – he was making $300,000 a year. I was paying more taxes, just like Warren Buffet’s secretary. He kept every receipt and when it was all totaled up, he paid very little taxes. It was by design: Allen didn’t want to pay any tax for war, so any money he paid he either hired secretaries, wrote off on taxi cabs, books, whatever, and basically he made about $6,000 a year after everything worked out and he paid no taxes.

Most of his reading fees were put into a non-profit, the Committee on Poetry, and then he gave that money away. So he supported a lot of people. He didn’t want things. He finally got a little T.V. (across Avenue A was a French lady who had a little video shop) and he got a little gay pornography, but that was about it. He didn’t watch T.V. People would ask him, “What do you think of Dobie Gillis, Maynard G. Krebs?” He would go, “Oh, Maynard G. Krebs – late 1950s stereotype of beatnik character.” He had a memorized response, but he never saw it – he wasn’t aware of it.

Allen’s East Village

People would always call Allen and say, “Allen, come to my shangri-la in Hawaii,” and here or there. He would never go. A vacation for Allen was coming back and having nothing to do in the East Village. He would often go to the poetry readings at St. Mark’s. He loved the mushroom barley soup at the Kiev. And The New York Times – he just loved it. He hung around Tompkins Square, wrote a lot of one-line poems about skinheads there. And he was a natural. I think because he always felt free here.

It always goes back to: it was inexpensive; he could always keep a home in the East Village no matter where he was, whether he was in Boulder or upstate on a farm or wherever. He would come back here in this room, at this desk here, look at the pile of papers and literally pull at his hair and go, “Oh, karma! karma!” and complain. But then he would stay up all night and go through the mail and start giving me a day’s work to answer these letters.

And I like his poetry about the East Village – “The Charnel Ground” is one of his great poems and it’s all about the people in this building. My friend Michael Scholnick died suddenly and that’s in the poem, and everybody living in the building is in the poem, and I think some of the bums he talks about on Avenue A are still there. Well maybe not, it’s hard to know when they finally go away.

The Houseguests

It was a crazy household. Peter Orlovsky was there; Denise Mercedes, who was Peter’s girlfriend then and started a sort of punk rock band called The Stimulators, was there. So there was a lot of activity here. It was an open house – there were always people staying here.

I always thought I was blessed that I was given this opportunity of getting to meet so many people. Dylan and Roger McGuinn in the bedroom, playing music. I talked to Paul McCartney on the phone. I met Dylan in person a couple of times, though I didn’t get to know him or anything. People dropped by – Ram Dass, all these spiritual kinds of people – but mainly the poets: I liked Philip Whalen being here and getting to know him – Robert Creeley, all my heroes.

Gary Snyder came by – he would stay here. Michael McClure. And Robert Frank. Lucien, Robert, and his brother Eugene – and then William, of course – were his closest, oldest friends.

I don’t remember seeing Burroughs here – Allen probably went to see him. He was deferential to Burroughs. He was 8 or 10 years older than Allen. Then when Burroughs went out to Kansas, Allen went to Kansas several times a year to see William. He loved William. The whole thing about the Beat generation: it’s not an art movement, it’s a friendship movement. They were sacred friends and Allen’s pictures, especially the early ones – he was taking pictures of his sacred friends. He didn’t even think of them as photographs.

He once came back from seeing William and said, “I’ve been thinking about gun control. If you have gun control, only the criminals will have guns.” I said, “Allen, that’s what people have been saying forever about gun control!” He said, “Yes, but William never told me before.” Anything William said had a lot of credence. He loved Jack Kerouac. I never met him, but I could tell he loved him.

Lucien Carr, who is the subject of this new movie coming out, “Kill Your Darlings,” was a wonderful old friend and he wanted to stay out of all the publicity. Lucien came by a lot and visited and I know Lucien’s kids and all that stuff. Gregory [Corso] stayed here all the time. I had a lot of interaction with Gregory and he’s a colorful, difficult guy. I was always proper, so if Gregory promised to pay Allen back and he didn’t, I got mad and I wouldn’t do anything for Gregory. That would go on for a little while, and then Gregory came by and said, “You know, you’re not a real poet. I’m poet-man, you’re not, blah blah blah.” But then eventually Allen would say, “Could you give Gregory his money – yes, Gregory.” I have the pictures of his little notes saying “yes, Gregory.” Because he knew I didn’t want to deal with Gregory anymore out of some principled stand. But then I would give in.

I remember walking Gregory to the bank – the Amalgamated that used to be in Union Square. I was cashing a check for Gregory, and I was saying, “Gregory, wouldn’t it be great if heroin could be legal and you could just have your stuff?” And he said, “Oh no, don’t you think I want to clean up?” Just like Allen wanted to be straight, Gregory wants to clean up! It’s five bags a day for decades but no, that’s his dream: clean up, and I want to get over it. Huh.

Diane di Prima would come by a little bit but I didn’t get a sense that Allen was that much into her poetry. He didn’t read the women that well. He liked Anne Waldman but I don’t even know if he read her that seriously – I’m not sure. But he said nice things about Anne because they worked together at Naropa and everything. But he liked Eileen Myles’s poetry actually, I think because she was gritty and earthy and direct.

Later on, the late Lita Hornick set up a reading for Eileen and Allen and I at the Museum of Modern Art, and she got me to read there. She didn’t tell me it was with Allen and with Eileen. The whole thing was fraught with issues for me because I knew Allen liked Eileen and I wasn’t sure if he liked my poetry. And I read and Eileen read and Allen read and actually Allen told somebody else he thought my poetry was really good. So there were times when he liked my poetry.

East 12th Street and the “Boys’ Dorm”

On our website we have one of Allen’s pictures of the block from the ’80s and it looks like a bombed-out city. This was a wild block in the ’70s, too – it was scary. Larry Fagin, after a reading, said to Shelley and I, “Come back to my house and I’ll show you some poetry magazines.” So we walked him back and then we realized he just wanted someone to walk him down the block. Because there was an old abandoned bus garage that was very dark and scary with weird people living in it. 419 was full of junkies and drug dealers. There were two Italian social clubs close to First Avenue, and then the Avenue A side was Puerto Rican gangs. In the summer there’d be gunfire. Big Daddy, who lived around here somewhere, ran a car chop shop right here. They would steal a car, bring it in front of the [Mary Help of Christians] church, strip it in a couple of hours and then in the evening fill it with garbage and gasoline and set it on fire. Everybody was on the streets partying and then the fire truck would slowly back down 12th Street. Everybody would applaud as it put the fire out, and then the hulk would sit there stinking for days. It was wild.

When Allen moved into the building, Larry Fagin said, “Oh, now all the Avenue B artists are going to move in.” It’s kind of true – the building filled up with young poets. To the point where in the ’70s, during the feminist revolution and all that, this became known as the Boys’ Dorm and none of the guys could get dates. It didn’t matter to me – I was married. But a couple of them moved out just so they could start dating. Because the girls who were poets themselves and willing to date other poets, they wouldn’t date anybody here because they figured, “Oh, gossip.” But Greg Masters who is upstairs is still one of those guys.

Very soon after, Richard Hell moved in, and my friend Simon Pettet. And upstairs was Arthur Russell, the musician who played with Allen, and above him Cornelius the outlandish black drag queen who would bring home really rough trade.

One time, Rene Ricard took me up to the roof in some kind of crazed state (I don’t know why I went with him) and he starts getting me to the edge of the roof, saying, “There’s where they do snuff movies.” And I thought, “Oh my god, he’s going to push me down that air shaft. He was crazy on crack, and just a month after that he burned his apartment. But he’s made a recovery of sorts.

Jim Brodey, who was a poet of the generation, stayed for a little while. He started to make a poetry anthology called “437,” of all the poets who had lived here, even just for a summer or a little bit, and it was really a big fat book. It never got published.

When we were in the 17 apartment, we lived right on top of where the Seeligers lived – the crazy Polish landlady who was giving one hour of heat in the morning and one hour of heat in the afternoon in the winter. They had some kind of concentration camp mentality. We had the tenant meetings over their head so we could stomp on the floor and then Allen and Peter would come down and they were the worst (this was before I worked for him, when we were neighbors). They would say, “Oh, they’re nice people, the apartments are warm.” Well, Allen’s was a warm apartment – it gets all this sun. They would say, “Oh no, it’s well heated,” this and that. We stopped inviting them to the meeting.

You would think Allen the great radical organizer … but no, not here. He didn’t want us to be too outrageous, but eventually we did take the building away from Mrs. Seeliger. The court did. The tenants ran it for a while and that’s how Allen got the third apartment.

Allen and Peter

Harry Smith would be living here and walking through and making films, and Peter Orlovsky’s brother Julius would be here. I would listen to music and then Julius would say, “Bob, would you like me to turn the music off?” and I’d say, “No, Julius, I’m enjoying this music,” and then 30 seconds later he’d say, “Bob, would you like me to turn this music off?” And after a couple of times I’d say, “Okay, Julius, I have an idea: why don’t you turn the music off?” Denise [Mercedes] and her bandmates would try to get Julius to swear and they’d try to trick him but he was so smart and they could never trick him into saying a swear word. It was really kind of zany.

It was kind of sweet in the beginning – Peter was making coffee and running in and handing it to me and giving me gallons of apple juice. He was just like that stereotype: had a Volvo wagon down there; he was living upstate and coming back and forth.

Peter had the other bedroom over there, and then later we acquired the 24 apartment and that was sort of the ejection seat. Whoever was breaking up got to live there and then they broke up and some strange things happened. When Denise and Peter were breaking up, Denise ended up there and they were finally done. Peter and Juanita [Lieberman] lived there and then that was finally done.

When Allen moved out, that’s when Peter moved back here [to apartment 23]. He was nuts then. I mean he was always nuts but that’s when all the pigeons were living here. They were walking all over the place. He kept the windows open and he fed them. Peter was true to his art – he was the kind of guy who would drink his first early-morning piss. It was like an ancient mariner kind of thing. I wasn’t sure how often he did these things or he claimed to do them.

I was often taking care of Peter – helping him take care of a parking ticket or get new license plates for his car. In 1984, when Allen went to China, I had to hospitalize Peter. He was very crazy and he had alcoholic-induced psychosis and that’s when he attacked me with a pair of scissors and tried to stab me in my crotch. I loved him, I loved that guy – until he threatened my children. And when he threatened my children, all the love just flowed right out of me like toothpaste out of a tube. I had never experienced any taboo like that but all the sudden I never felt the same again.

I busted him and I don’t know if you remember the Eleanor Bumpurs case – in the Bronx, a big heavy black lady was being evicted. They came to get her and she expired. The police didn’t handle it right. This was the next week. I called the police and Peter’s in here. The police come and Peter was naked with a machete in his hand and he was chopping his own hair off. I mean, he was going in – there was no doubt. And he said, “Let me go get some clothes,” and we said, “No, no,” and he zipped back into the 24 apartment, locked the door: hostage. And that went on – there were cop cars, T.V. stations downstairs. And he wouldn’t do anything.

We finally got one of the Buddhist community guys to come over and he said, “Peter, can I get you something? a bottle of sake?” He was really drunk on sake. And that was the face-saver – he opened the door for the sake and then the police all flew in, strapped him to a chair, and carried him down the stairs. He was screaming like a banshee, playing it up. They got him to Bellevue and I wrote Allen a huge long letter. It was one of the emotional centerpieces of my time here: I was threatened; my children were threatened; I had to take action; Allen couldn’t be here. I always figured Peter did this to me because he knew I would. I mean he had to sober up and he couldn’t help himself, and I think it was a cry for help.

Allen loved it all because it reminded him of his mother’s old episodes. He always kept files on Peter. So he was really the enabler to that kind of crazy behavior and he got a special glow going. I was really naïve at first: when Peter would spend a couple of days in his room, Allen would say, “I figured out what Peter’s doing – he’s drinking,” and I’d say, “Oh no, really? Drinking?” I was naïve. Allen knew he was drinking – Allen knew him for decades. It was just the game.

After this harrowing experience, Allen came back from China and I had read “Straight Hearts’ Delight” and I saw them as the pioneering gay couple and all that, but I always knew that Peter was actually more straight than gay. But still I saw them as a gay couple and I said, “Allen, I don’t understand this relationship.” And he said, “You know, it was only good in the beginning, really” – when they were both really into it.

I get the sense that when Allen first met Peter, Allen just let himself go on Peter. He was like 28 years old and it was the first open sexual relationship he had. Peter accepted Allen, and it was great. That’s when Allen writes “Howl,” and I don’t think Allen writes “Howl” without having Peter. But really soon, Peter in his notebooks is talking about girls on the beach and Allen doesn’t like it. And then Allen realizes, if Peter gets girls then Peter will service Allen, so it becomes a service relationship.

And that was the revelation for me – that it was this one-way relationship: Allen pays, Peter serves and that’s the way it remained. And then eventually I don’t think there was any sexual serving, it was just that Peter would be nice to Allen for a little bit and then he’d get some money. But Peter always had his VA money and after Peter’s drug and alcohol and crack and speed and all that stuff, he would get the check and just get bombed for days and days and days and days and then run out and then sober up hard, and then the last week be self-loathing and remorseful and then the next check would come in and he’d start again. He was bombed, walking up the middle of Sixth Avenue in traffic, yelling his head off. It’s incredible that Peter lasted longer than everybody.

Allen’s Other Loves

He had a lot of boyfriends. He mainly liked straight guys and a lot of them were students. He liked straight guys who would make a special accommodation for him. It’s kind of a problem in the old-guard gay society. Later in his life he actually started to have relationships with gay guys and I thought that was an improvement. There were steadies and this and that and loves. But you know it’s interesting: he would come over and I’d be working and he’d come in with some kid and he’d go into his room and he’d say, “We’re going to go meditate” and I’d say, “Oh yeah, right” – but actually they did. They did both – they probably made love and then meditated.

He was definitely cock-driven – he was definitely on the prowl in a way, but he was not a pedophile. The age of AIDS was actually beneficial to him. Because of his diabetes he had a condition called disesthetia. He actually had a lack of feeling below the waist, so it was very hard to have an erection later in his life. So the point was getting in bed, do more Whitmanic snuggling, and talk about what you’re going to do, and the talking was good and this and that. And so in the end of his life he was doing more snuggling and cuddling and stroking and kind of friendship stuff.

He has some very graphic homoerotic poems. I’ve talked to gay friends about, “Is it really homoerotic? Is it erotic to you?” and some say, “Oh, yeah,” and some say, “No, it’s just self-serving. It’s stupid.” I would probably agree with the latter. I don’t think his “Sapphic Verses” are his best stuff. He wrote a lot. But still, at the end of his life he wrote beautiful poetry.

Allen’s first name was Irwin, so I had moments with Irwin. Like if I was driving him in a rental car – this was before cell phones, nobody could call, nothing could happen, and those would be these private moments. Once he said to me, while we were driving someplace, “Don’t you think if I could just take a pill and be straight that I would do it? I would get married and she would do my laundry and feed me and take care of me?” And I said, “Allen, it’s too late – that’s not happening. Don’t take that pill – it’s not worth it!” And you know what, I think he was just saying that for my benefit, just giving me a clue into him.

Allen in Conversation

Allen would do circuits – he would go on the publishing scene, the high-powered art scene (Henry Geldzahler and all those guys) and then photographers and then musicians, and he’d go from circle to circle to circle, so he kept going around and around.

He loved the East Village more than any place in the world. He would walk down the street every day and people would just say hi. They didn’t stop him or make demands or ask for his autograph, they would just say, “Hi, Allen.” And they were just happy that Allen was in their world and part of the neighborhood. When Allen died, I was dumbfounded how many times within a couple weeks people who saw me told the same story: “I said hello to Allen and he said hello to me.” At first I was really puzzled and I thought, what is going on here? Then I realized he wasn’t just saying hello, he was stopping, he was bowing, he was saying hello to the inner bodhisattva in them and that’s who heard them and that’s why it was so memorable – because he got right to the core of their being and said hello to their inner core. It means something.

That’s what Allen was about – his greatest art form after poetry was the art of the interview. If you were coming to interview him, he would hector you: “Do you have your cassette recorder? Do you have extra batteries? Do you have extra cassettes? Are you ready to do this interview? Do you have real questions? Have you thought about the questions you’re going to ask?” Then the interviewer would get nervous and then finally they’d start their conversation and Allen would just open up and be outgoing and not know when to stop. That’s why they’d need extra tapes – Allen knew. And then Allen always demanded that he gets to edit the interview, or he get to look at it. And then he would never have time to look at a transcript and the guy would be like “I have to publish it!” and I would have to get him to do it.

I think that one of Allen’s greatest books is the book of interviews, “Spontaneous Mind.” I think his prose writing is kind of esoteric and it’s a little hard sometimes because of the way his mind jumps or because of his odd punctuation and syntax but when he talks, he’s talking to someone’s bodhisattva so it’s all really direct and he’s really communicating. And that’s why when we did the “Howl” movie – I think the best parts in it is when Johnny Depp is reading Allen’s interviews because I think it just communicates so well and so directly to the audience.

But Allen explained it to me – he didn’t explain how to do it, but it’s something I try to do and I think it’s by being polite, by assuming there’s a bodhisattva in everybody and starting right there. I think that’s how he made peace between people and he could get angry Hell’s Angels to not beat up demonstrators and things like that. He’d just talk to them and be natural. Mailer called him the bravest man in the country. And I think it’s that. Allen’s hero was Myshkin in Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot”: somebody who’s seemingly naïve but he’s just so genuine, and everybody opens up to him because they just can’t help themselves. Allen was really deep that way. He was special, definitely.

Allen’s Addictions

Allen always had some pot around – he was a pot propagandist and so if a joint was being passed around and someone was going to take a photograph he would grab the joint so he’s got it. But actually, I rarely ever saw him smoke. He had pot for boyfriends – it’s a good line: “Oh, you want to come up and smoke?” It was really for them. He would go to LSD conventions with the big guys – the Fitz Hugh Ludlow Library guys, Huxley and all those guys. They would give him acid and he would come home and put it in the refrigerator and that was cute. There was a little vial of LSD and it said “Do not take without permission of Allen or Bob” – so I guess Bob had permission. So that was nice. But I never saw him on LSD.

He was a workaholic. He didn’t like alcohol – it killed Neal and Jack and Trungpa. And he didn’t like speed. He had a set of works in his drawer under the bed. I actually still have that because you can’t sell that stuff. We have the drug paraphernalia – some nice roach clips and things like that. And I’ve had European buyers, but I’ve said, “I can’t send it in the mail,” it’s actually illegal. So I said, “You have to come and you have to get out of the country.”

One of the things Allen said to me before he died was, “Don’t make a museum out of me,” but when we moved out of this apartment we had a tool box and I put in all this little bric-a-brac (coins he had gotten, little medallions he had been given, things he got while traveling, his drug paraphernalia) and I call it the Beat Museum. It’s kind of a joke but it actually is – it’s a little treasure chest full of oddities. And so we still have that.

But no, Allen was a workaholic. So he always had Demerol and that was so he could get up on the stage and read, and that was so important to him. Above all things in this world, he loved to get up on the stage and give a reading to college students. It wasn’t the money – it was the applause. It was the communication. My pop psychology sense is that he had this psychotic mother, Naomi, who had her first breakdown even before he was born. Maybe she couldn’t mirror well, maybe she couldn’t give him a proper well-balanced narcissistic self so he needed affirmation – he needed applause. Luckily he doesn’t go around shooting people to get attention, he wrote poetry to get attention. And great poetry. And got great amounts of attention. So it was all really good.

But even when he could’ve stayed home and taken care of his health, he went out and did readings. Readings he just could not say no to. He could’ve just sat at home signing his photographs and made more money, but it was never about the money, ever.

The Million-Dollar Question

When he made the sale to Stanford, he got attacked in the New York Times three times, in three different sections, three different ways. Some guy wrote an op-ed: “Oh, well he should’ve given it, blah blah.” I mean he was living here – he could barely make it up these stairs. I got Simon downstairs to agree to be on call whenever Allen was coming in at 3 a.m., to help Allen carry in his bags. But you would walk up with him and he’d start telling you a story and the middle of the story would always be about Kerouac or something – “and then Jack said…” – and of course you stop and you lean in, you want to hear that story. He’s just breathing. The whole story is an excuse to catch up on his breath. It was so hard.

It was really important to get him in an elevator building – why shouldn’t he have a little comfort? I truly tried to figure out why there so much anger. And I think it’s that basic east-west rivalry – that it should’ve gone to the Berg [Collection of English and American Literature], but we got screwed by our book agent who said he had approached the Berg at the New York Public but he actually never had. And I don’t know if the Berg would’ve bought at that time.

Stanford was in acquisition mode – they acquired Levertov, Allen and Creeley all really close together. And they paid a price, and they didn’t quibble; and it’s a new building, it’s air conditioned and well cared for. It’s not a bad thing. Ironically at Stanford is the Hoover Institution, which has all the paperwork of the former Soviet Union, so it’s kind of fitting that all of Naomi’s paranoid hallucinations would be documented in the Hoover Institution and there’s Allen’s papers right across the hall.

The Gap Ad

In the Gap ad, there’s a very small disclaimer that says all the money is going to the Jack Kerouac School. It actually got Denver impoverished youth a summer program at Naropa but it didn’t matter, people were really mad because I think Allen had a really pure persona – he was above it all, he wasn’t commercialized. William Burroughs had all sorts of ads, actually. Nobody cared. It never mattered about William but with Allen, people resented the idea. Allen had to walk around with this persona he created that was a mixture of pure and earthy – he had to live with that.

Allen took money from the Rockefeller brothers and gave it to Naropa – his idea was very much akin to Chögyam Trungpa’s idea that you take the bad money and you make it good; you take in the poison and you breathe out the nectar. It didn’t bother him. It just rolled off and it didn’t last that long and when Microsoft used the same picture in some kind of ad (I’m pretty sure it was Microsoft) when they figured out he was using the money for charity they doubled him up. And so $10,000 became $20,000 – that all went to Naropa. It was good. I think people in the world of money understood and they liked the idea.

Allen on Film

I think a lot of “Kill Your Darlings” is taken from his journals, so I’m hoping it’s more of an intelligent treatment of the story – less sensational. He liked David Kammerer. He was sorry that David Kammerer was killed. I think it’s going to be a little bit more even – it’s not just going to be the “honor slaying.”

His experience with the movies was when they were making “Heart Beat,” the Carolyn Cassady story, and they sent him the script and there’s a young Allen Ginsberg drinking coffee and pounding at a table going, “Moloch! Moloch! Moloch!” And he was so offended that he said, “Take my name out.” So they left the character in and they changed the name, but it was something close; and he realized it’s better just not to mess with it. You can’t control it, just let it go.

One thing I’ve noticed: Allen always comes out reasonable and nice in these movies. He’s always seen as the sane person. And I think that’s the way he really was, I guess, even though Kerouac’s treatment of Allen is not very complimentary in “Desolation Angels.” The Carlo Marx character is obnoxious and I think he truly was an obnoxious young man, but he was so young and I never knew him then. I only met him after years of Buddhist meditation. He had calmed down.

When he wanted to get angry about plutonium – the Rocky Flats trigger factory in Colorado – he wrote it, but he couldn’t find the old anger, he had kind of meditated that anger away. So he had to create anger through craft and editing. And I think “Plutonium Ode” is a really strong poem and it has great parts and I think the fourth section about advice to the poets of the future is really spectacular. And it stands up well. It’s like a baseball pitcher; you get a lot speed when you’re young but then you have to learn how to pitch.

Watching Allen Work

Neither Allen nor I could spell. I was so lucky to find a boss who couldn’t spell either.

I didn’t presume too much to tell him how to write – he was pretty much always the master. But I got to contribute to some of his poems. Like right at the end when he wrote “Death and Fame” – it’s a poem envisioning his funeral and what everybody says. I remember I was going with him to Boston to see his cardiologist. It was at night and it was raining. It was one of those cab drivers who was driving too fast and stopping too short and I was getting seasick and Allen said, “Here, look at this.” He’s showing me the notebook and I said, “Allen, I can’t read – it’s dark.” So he starts reading it to me and he’s breaking up and laughing and after I heard a bunch of it I said, “Oh, and the girls say, ‘He never did know my name,’” and that line made it in.

I think on the liner notes and things like that I would have input but otherwise, not so much with poetry. That’s Allen Ginsberg – I’m not fussing with it. I was happy just to be able to type it. On the plane that same time he fell into a deep sleep – I mean, it was like dead asleep; I was actually worried whether he was going to wake up – and then he woke up with a start and grabbed his notebook and wrote down a little couplet which is actually in one of the books. I don’t know if it’s collected in a group of poems but it was “my father dying of cancer, oy, kinderlach, the little kids,” and that still kind of stunned me – here I am witnessing this. I think I was always a little bit in awe of Allen, though very comfortable.

I never showed him my own poetry and I don’t know how I was smart enough not to do that. I know he had his own protégés and I realized I had to promote them and I didn’t necessarily always like their poetry and it would just make it hard if I was jealous of them. I think he was relieved that I wasn’t foisting that between us.

The Last Soup

Allen liked to cook soups right here at the sink. He liked to go shopping. When he was on 13th Street, I had a guy set up to be his car service chauffeur, I had a housekeeper who did all his cleaning and shopping for food, and he had a bathroom with a bidet.

Everything was laid out and open and he designed translucent windows between rooms so that the inner rooms would get light and not have to be lit by overheads. And there was a mud room when you came in so there was a bench and cubbies: you’d take your shoes off when you come in and stick them in the cubby. He was in the big room – he had the office in the back. I learned how to check his insulin, how to shoot insulin – I was trained by a diabetic counselor. And I was going to marshal his time as a resource. So if someone came in to interview him I’d say, “You have 90 minutes.” I’d come in at 90 minutes and cut it off. I would save his energy. The world would come to him. But we only had a couple of months of that.

One of the last things he did in his life was he had this soup. He called my wife. She had a made a fish chowder for him and he liked it and so she gave him the recipe. He liked seafood, so he went out and he got all sorts of clams and scallops and all sorts of seafood and he starts throwing it all in, with the clams in the shells – I don’t think they were really washed. Usually he was very sanitary about things but this was his last soup.

One of the things he built in the loft was a soup cooling rack outside one of the windows: it was a rack that hung out there so you could put a big pot of hot soup out there to cool – a unique feature in anybody’s apartment. So he made this soup and I refused to eat it but he served it to a couple of people and they said it really wasn’t very good. And then we froze a lot of it and then he died.

I cleaned out his apartment and one of the last things I cleaned out was his kitchen – it was actually, strangely, the most emotional. You’d think his library would be, but no. His spices, his dried mushrooms, his supply of peppercorns, all that stuff – that was really moving. His cookbooks and then the soup in the freezer. And I thought, “I can’t throw this soup out. It’s like there’s something about it that’s interesting.” I knew that food anthropology was kind of a new thing and I thought maybe somebody would want it. I had a friend Jason Shinder, who has unfortunately passed away, but he was a genius; ran the Writer’s Voice at the Westside Y for years and could really figure things out. I gave him a task: find a place that’ll take the frozen soup.

He actually did – it was this museum of oddities in California, but because of earthquakes they couldn’t guarantee that the electricity wouldn’t be cut off to the refrigerator and so they ended up not taking it. Meanwhile there was a squib in the New Yorker about Allen’s last soup – that was fun – but I still just want to do a movie where you get a food anthropologist and bisect it, talk about it. We have the original shopping list for it, the housekeeper who bought it, and Shelley could talk about it. Now it’s in my freezer on 10th Street where I live.

Last Poems

He became a little addled and he was writing nursery rhymes. He asked me to bring a copy of “Mother Goose” and I went through my kids’ old books and I found my old “Rackham’s Mother Goose” and brought it and he was looking at it and said, “Oh yeah, see? This little piggie went to market, this little piggie stayed home.” Then he said, “What about that third little piggie?” And I said, “That little piggie had roast beef,” and he said, “Ha! Pigs don’t eat meat! It’s a change.” And then he rewrote it to say, “This little piggie had quiche.” Of course, he’s wrong, pigs eat meat – but that was beside the point. He was rewriting “Mother Goose,” and rather well.

And they were flowing out of him – three or four poems a day at the end, until he finally got the fatal diagnosis that he had months to live and then he only wrote one poem in a week, and it was a poem of regret. On the website you can actually see a holograph of that poem. It was the only poem he never got to see a typed copy of to correct, so there actually are some words we never figured out. But we think we have them all now.

[Originally published by The Local East Village Blog-NY Times, http://eastvillage.thelocal.nytimes.com/tag/straight-around-allen/.

Retrieved 4/26/2012, 4/30/2012 via first notification at Our Allen Facebook group, https://www.facebook.com/groups/65164414719/, 4/26/2012.]