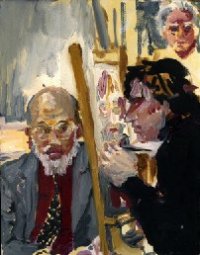

ROBERT LAVIGNE

THE ARTIST'S LIFE AS A WORK IN PROGRESS

Fifty years ago, I walked in the October fog of SF, and for the first time in my life, felt I was home. Until a few years ago, I thought it was just the warmth of the mist enclosing me, hiding me, as it did the buildings which disappeared into it, leaving their architectural details visible only as shadows to my eye. As everyone alive then, I was confronted with a Reality that could be vaporized in a moment.

As an aspiring artist, I came to that city for its standing as the "Paris of the West" (I believed the town's PR; its next pitch was as "The Athens of America" for someone's 'Great Books', with "philosophers strolling the streets talking great ideas", in Pacific Heights yet). Foremost in my mind was painting. Till then, my training had been in the physical and chemical construction of the surface (to be more than a coat of lipstick), to make works that justified their existence by attending their owners for their lifetimes--being there as a stable reality for those who wanted to compare the past experiences of their minds with present ones.

The Atomic Age gave the lie to permanence. How then to make durable works of art when there is no future for them to endure? I was paralyzed by the question, pacing my small apartment in the age of anxiety.

On a sunny day that fall, I was on Divisadero Street (oh, the exotic names!) where there still were bins on sidewalks in front of shops. Strolling two blocks from home, the (still to my eye) startling phenomenon of California oranges in sunlight arose from one of those bins. Abutting it, a bin of schmatas outside a yardgoods store with a tag end of blue taffeta, big as a diva's hanky dropped next the oranges. It caught my eye, till then, trapped in the orange bin. The two were made for each other. I had discovered Cadmium Orange! I bought both and never looked back, had fallen in love with light bouncing from objects. No matter how impermanent these things were, their beauty kept my mind from too much reflection on the problem that plagues our age. For awhile, they would hold my attention which would then shift to problems: Ideas, and how to paint them, and the nature of the materials I was using and how to make problems interesting enough to solve. A solitary apprenticeship.

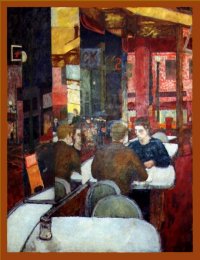

Among those early discoveries in mid-century San Francisco were newsies calling out their paper's name in Chinese! enroute to the Black Cat Cafe with paintings on the walls! And only two blocks away from a cable car which the town's government was trying to junk for better automobile flow. At the Black Cat, I encountered an habitue I'd met at a boho bar in Seattle. A month or two before, back there, I'd seen her dance, after enough drinks, in her Doris Day pink linen duster and sheath, the latest fashion. And don't forget matching hat and shoes! When she'd lift her skirt there was no underwear beneath. She had been interested in portraits I drew of tourists. When I told her I'd begun to paint, would she like to see what I'm doing? she invited her NY to stay at my SF digs.

Then began some serious instruction: a truly stable medium and some serious sideline qvetching on care, caution, and other matters of practice.

"Knife all that medium into the paint!"

"Test the color on your brush before you put it to the canvas."

Most important, she introduced me to paintings by modern masters and began what might have been a terrific practical exploration of the history of modern art, but that I was too busy making some myself, and too young and dumb to realize I'd found a Teacher. Who posed nude, yet.

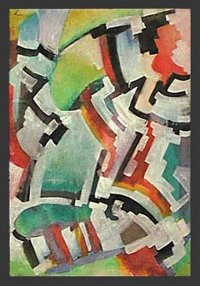

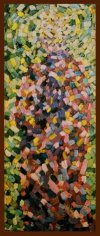

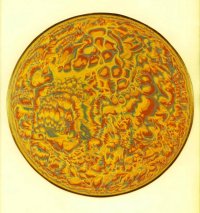

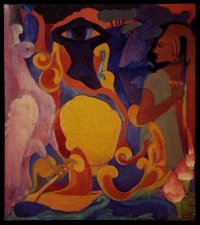

She had dipped me into the paint of Divisionisme and I was launched into a sea of spots:

I used to think she left because the food and booze ran out, but later, I'd sometimes think, she gave up on me.

I came to realize I belonged in North Beach where the Black Cat had paintings on the wall and sawdust on the floor! There were, to country boy eyes, wonderful people. Old Barcelona, round and barely five feet tall who in his rags, would say, "Eef you zee me one thee strate, you don' know me." Someone would call him a Fenian and he'd respond as to an insult. Guy Wernham and his grown children would come there. Jimmy the pianist who'd as soon smash a nasty antagonist in the face with a glass of the rye, neat, he drank exclusively. William Saroyan (who'd lived in the Montgomery Block of ateliers, levelled for the ostentatious pyramid there now) was rumored to have carved his name large on a tabletop, later to be protectively covered over with the plywood whereon our beers sat.

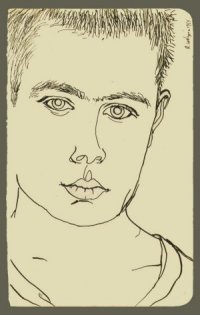

I joined the portrait 'club'. I'd made them in Seattle at the Double Header bohemian, sailor, college slum bar, really a tavern in those days of beer and cheap wine for non clubbies in dry Washington state.

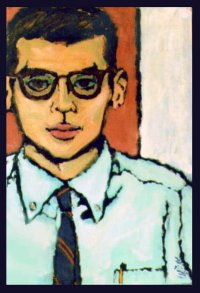

Making portraits for a few dollars exploited my natural talent for the human face and left days free to paint in my tiny studio in the building now known as Columbus Tower and permitted the extended study of a model who was paying to sit. Eventually, my eye's honing was such that I would find myself going deeper and deeper into the study of a face, taking a lot more time than I was being paid for, into hours. But I was looking closely at reality. Thinking back on it I know that drawing is, as well as a training exercise of the 'pitching arm', a permanent record on the artist's brain of the experience of looking and seeing. Recording, stroke by stroke a world that can be referenced, throughout the brain, it trains itself to notice all of reality at a glance; and from that habit, ability to see and instantly record imaginings and visions, all their details without having drawn them.

Clay Shaw who'd loaned me John Rewald's Study of Impressionism, now puts John Rewald's critical biography of Cezanne in my hands. It was an opening to several practices of my life that have remained with me. The first and most important was to affirm my own habit of working the surface all over, but to refine it with architectonics. And, I had watched my eye come to see more and more in prolonged study of the human face, and the world. Oh, for those times one could decide to see nothing but ears for the day. Or the outer fold of an eyelid. On other days, nothing but cobalt blue or mixing in one's mind, pigments to replicate what one is seeing in nature or in town.

Initiating a drawing with blue was another of the insights that came from Papa Cezanne, to see light embodied in that narrowest of the color bands of the spectrum and match that luminosity throughout the work.

The influence of Oriental Art on the West Coast pointed us to inner change growing from the idea of a long meditation to make a fast painting pointed up to us the importance of one's inner life. We wanted our work's Style grown likewise from our insides out onto the canvas, the page. It meant to live one's life with all the shapeliness of Art, to live with the intensity art-making required. Someone reduced this view of practice to the term 'Life Style'.

My mother, from the flapper era, who, in my childhood during the Great Depression, spoke to her younger sisters of their "drinking and smoking and carousing around", sisters whose aside would be, "Well, who do you think you are, Lady Jane?"

She had "chums" whom she addressed as "O kid!". Later, when I reached the age, during World War II, of such sanctions, the line was,

"What do you want to do, join the Lost Generation?"

I went promptly to the dictionary and then the library, uncovering its history. O! What glamour! While there, I found Baudelaire, Hart Crane and Ezra Pound's Make it New, which for writers, I read as if it had been written for me alone, as I thought then all books had been. Pound's translation of Fenellosa's enlightening essay The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry turned pictogram to landscape in my mind, widening its scope to accommodate the view.

In my life ten years later grown to twenty-four and painting, that essay that had opened a door to me (as it must have to every artist who encountered it) into the difference between phonically sounded letters to make words and ideograms to picture a whole idea. He showed a poetic thought put into that symbol, the descendant of a pictograph; led us to its ancestor, pictures of things called drawings. An abstract concept and the history of that concept's formation from some place or thing in nature, is preserved in its ideogram which resembles its ancestor whose essence is pictured in the work of Art before the viewer's eye.

Such is the service we need in our present and coming struggle to keep alive present-day knowledge of the dangers of nuclear radiation, a culture of etymological intelligence through which past knowledge is contained in the modern tongue.

Good Friday, 1954, my neighbors and a few friends and I dressed in unrelieved black (as Existentialists and Boppers were wont to do). The girls added black lipstick and eye shadow. We did the rounds. We met at Foster's Cafeteria, where unknown to me then, Peter Orlovsky sat reading. Later, after we became lovers, he told me he'd been there, seen us.

"I Thought were you were Communists."

Later in the spring, I noticed him seated at a table, reading, and thought what a shock of Hair on that beautiful guy. I joined my friends at a distant table for awhile. On my way out, Byron Hunt was sitting across from him and stopped me as I passed. He introduced us. Byron had introduced himself to Peter, only moments before.

"You forgot to shave."

"What are you reading?"

"Franz Kafka. The Trial. Its about this guy who wakes up one morning, and he's arrested."

"Come see my paintings."

Peter writes from New York, where he's gone for his twenty-first birthday, that while drinking coffee in Horn & Hardart on 14th Street, a young woman came to his table and asked him if she could drink her coffee with him. When she remarked the shirt he was wearing, one that I'd made him before he went back there from San Francisco, she asked him where he got it. He told her his lover had made it; that his lover had taken hours moving lips along his body to find where the seams should lie.

What a surprise to know from the first love letter of my life, I'd not been forgotten. Then, to have one come daily, with such fanciful reconstructions of our short life together. Then they stopped. And then he was back, one morning, at my door. But why did he burn those beautiful letters from that summer at home in New York?

At a time when the average person didn't own a TV 'set', it seemed no oddity to see semicircles of people gathered before appliance store windows, watching twenty or thirty black and white TV sets, arranged in banks like canned goods, or the panorama we see behind the blonde debutantes (and a 'most sexy man' talking head with back fence yentl emphases) who now circulate news of the 'latest'. The haze of being in love with Peter directed my eyes elsewhere until it hit me in the face at the tobacconist's, where the greasy black and gray image of the scowling senator from Wisconsin (and his cuties, Roy Cohn and David Schine) was badgering a witness before his committee with the same contempt I was getting from the shopkeeper I was paying nineteen cents for my pack of ciggies.

A glance at the next pass of a TV store made it clear what the attraction there was, and why we were being spat upon and glared at by the wrinkled old apartment dwellers of San Francisco. It was my good fortune to be buying my pack of Fatimas (Fah-tee'-mus), one day, when I heard,

"Sir. Sir! Have you no shame, sir! Have you no shame?"

Back on the street, it became noticeable within hours that the police were no longer at one's shoulder to see whether we were on or off a curb before the traffic light turned green. A while before Mr. Welch's stunning remark and that grand moment in US history made theatrical by the new medium of television, I'd gone, on Clay's recommendation, to see, at a new theatre company called Actors Workshop's, a staging of Arthur Miller's The Crucible (which had gotten the 1953 Tony Award) in an old warehouse in the Mission district where I'd gone earlier to see the same company do Sophocles' Oedipus Rex. At those moments richest in meaning to that shameful era of the past attempting to arrest the future we were living through, I heard a hundred other people laughing or gasping at the same time as I, and it consoled my heart to know that I was not alone in my distaste for the mean spiritedness of those competitive forces in our society. It is not necessary to be barbaric to prepare to meet barbarians. The Crucible dramatization of the Salem witchcraft trial showed Americans how very impolite and un-politic were the actions of the very politicians on the tube daily.

I was heartened to know that my neighbors and I were not alone in our beliefs. In gratitude, I went to see Herbert Blau, Professor and Artistic Director of the new company, in his little office at San Francisco State College. In gratitude I volunteered my services, knowing for the first time, the power of theatre to relieve suffering in society's mind.

"Well," he said, "our restrooms need painting."

It is no wonder that the Hungarian Revolution in 1953 was launched from the stages of its theaters. The Living Theater enacted the diagram in Paradise Now, made in their exile to commemorate Paris's 1968 uprising that unfolded from the Odeon with its doors bricked shut against state violence. And the Velvet Revolution was bicameral: between the people in the 'house' and those in the green room of Vaclav Havel's Magic Lantern theater in Prague.

Reflecting on this time in America, I think back to the beginning in the 1940's after WWII when the ruckus over Communism began in earnest. Odd that Communists should be searched out in government so soon after a time, joined with them, we and the rest of the civilized world had to defend our nation against Nazi Fascists and a Kamikaze military bent on world domination. I'd thought, before my Army service, that cries against communism were just part of Sunday sermons from the pulpits of the Church. Harry Truman called the congressional brouhaha a 'red herring', and now I think on it, within the decade, Dwight Eisenhower in his farewell address to The Presidency had named its perpetrators 'The Military-Industrial Complex'. Already, in 1954, cries against 'planned obsolescence' (son of 'bombs wear-out-faster-than-Buicks') were sharing the front-page with maps of the Bay Area overlaid with concentric circles of dotted lines. Each circle signified a level of destruction outward from detonation of an Atom bomb above a bay turned to steam. They listed the number of deaths, with everything for three miles flattened. The rich moved out of town.

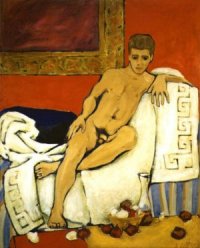

Peter helped me build an installation to show paintings that fall in my second show at Keller Gallery on McAllister Street, a block from the Veteran's Memorial Museum on McAllister Street (San Francisco's equivalent of New York's 'Orchard and Rivington' district) buried behind City Hall and The Opera House. By then, Allen who I'd met a month earlier (thinking he was trying to pick me up, not knowing he was on a search for the old bearded painter with the beautiful boyfriend) was living with us. He buys a drawing of himself, Peter and Natalie from the exhibition. Nude With Onions was first shown there. A lady approached me as I stood by the painting with John Keller who introduced me to her. After some opening remarks, she asks me,

"What's that between her legs?"

Allen brings home a bottle of Courvoisier on New Year's Eve. I come from work to join Peter, Natalie, and him for a pleasant kitchen evening celebration. I awake before midnight in a stupor. I wake Natalie. No sign of Peter or Allen. There's half a bottle of Cognac left. We stand on the front steps to see the starry new year come in. I'm devastated behind the smile as we toast the new year from the stairs of 1403.

Our household was broken up (or down) by reshaped relations, and all of us moved now to the Wentley, three blocks away where we no longer really lived 'together'. That is, no one to take care of or be taken care of. Fosters Cafeteria is our living room. Between there and The Place, it feels like we're in some odd cafe society.

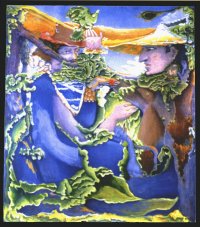

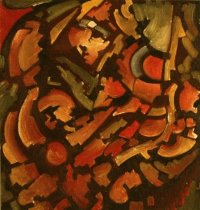

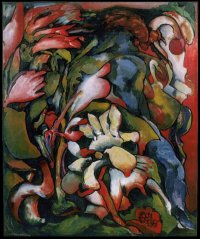

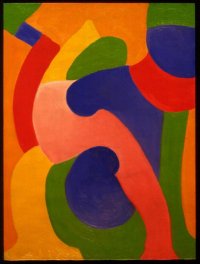

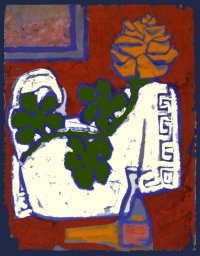

My pain was that of being odd man out, as I longed for the closeness of relating to one Other. I missed the odd turns of mind that Peter brought to my Jesuit formed thought. In a surprising turn of my work after a weekend in the country, I reached out to that past in 'The Flower Inside', followed by 'Iris Natasha'. Then, bitterness of abandonment asserted itself in 'A Rose With Thorns'. When the high spirit of that group of paintings became apparent to my eye with a show in mind, 'A Rose With Thorns' seemed too mean a work to include. Allen liked it, asked for it and I gave it to him. Now my friend Damion has bought it at a Sotheby's Auction and it seems strange to see it in an apartment on Capitol hill in Seattle, having hung all these years pinned to the walls of Lower East Side kitchens.

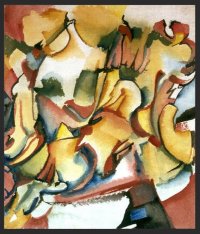

The earlier experience painting oranges seemed a pattern repeating itself as I painted my way out of the emotional devastation of love-loss, at work among colors. The new works brought poems from friends energized by 'switchboard central' Ginsberg, that were slid beneath my Wentley door. Late into the work on this group, an exhibition materialized around one of the periodic invitations by Leo Krickorian to show with him. It kept my mind occupied in this age of sadness until August, when I went 'abroad' to Mexico, relying on literature's 'cure' for a broken heart.

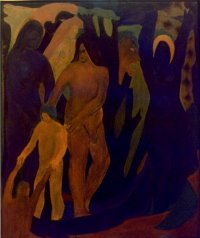

Natalie Jackson's fall last year from the roof of the building where she and Neal lived, came forward in my consciousness as I began to sketch for the large memorial portrait of the writers central to the scene that Ginsberg had created in San Francisco. Natalie had been so central to all our lives for her short year with us that she seemed an integral part of any record of the time. It was somehow her spirit, only one of all the dead I already knew by then, that ultimately suffused the final painting.

On the floor inside my room at the Wentley is a little brown paper bag containing six peyote buds that has been thrown through the transom above my door. I know what they are, because there is a note from Allen and Peter near them that's told me how to prepare them. Allen writes to take them with ice cream. I had no money for ice cream and I liked raw potatoes which the note likened to their taste, so I sliced them thin and ate them with tea. Let me tell you, peyote tastes only very remotely like potatoes.

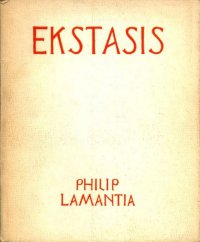

That trip was very low level. Inexperience led me to expect more and fail to fully understand the wonderful subtlety of the things that were happening. I remember the sound of Mexican banana leaves scratching one another in warm breezes. There are gigantic red lips, flexing like soft lipsticked muscles, speaking to me silently from a dark tropical landscape, throbbing in the space of their own picture plane. I think I hear Philip Lamantia, who lives next door, drumming on air surreal with the rhythm of his poems.

Today, January 12, 2001, I call Ira Cohen in Minnesota where he’s gone to sit with Gregory Corso, ailing from cancer and being cared for by his newfound daughter, Sheri. We talk, the first time since New York of 1998 for dinner at the presentation of AH Allen , Anna Condo’s memorial book to endow the Ginsberg Scholarships at Naropa Institute. How well he looked then in his velvet suit. How beautiful and loving his voice sounds now, writing his way through death. He lived onward from Fosters, past twenty-nine and into Poet Wisdom!

Samuel Beckett first came to my attention in the early fifties when friends who'd made Paris already knew of him, beyond his service as James Joyce's secretary, as an important writer. I was lucky enough for awhile to own a copy of An Exagmination Round the Factification of an Examination of a Work in Progress with an essay by him on Finnegan's Wake, the work in-progress of the title. Now, when I came back from Four Lakes to vote in he 1956 election, Waiting for Godot was playing at Actor's Workshop. It was the sensation of San Francisco.

Godot was a play that had me hanging off the balcony as I had years before at Long Day's Journey into Night. But Godot wasn't dealing on its surface with the relationships of family life. Plot was more like philosophical equations stated in a sad junkyard enactment by Vaudevillian comics. At last, there were people on a stage bare of all the goodies we were afraid of losing to the bomb, engaged in dialog that seemed to be asking the questions that concerned me and my friends. I'd seen a play that left my mind reeling with excitement.

Waiting for Godot was a work that completely suspended my disbelief. Imagination, stimulated by philosophical questions, worked, as I would soon discover, using surrealist method, to reveal that the concetto, buried in the electrical scars of our nerve calls, is as fixed as that in the stone of the quarries at Bibemus or Cararra. The dialog of Godot, very general in its terms, is as precise as philosophic propositions. It masquerades as everyday generalities. Each audience member's own psychic storehouse took a new meaning home. So rich was the experience, that repeated viewings, as in all theatre, led to multiple experiences of the a play which lent itself so to a novice theatre-goer, but meant and ultimately was seen by attentive audiences to represent the futility of such exercises. Each experience proved futile upon the next viewing, until the process of any interpretation could be seen to result from any performance, and that to interpret was as absurd as waiting for life, let alone Godot.

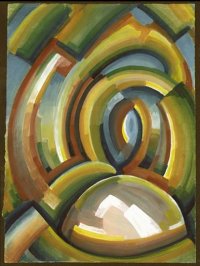

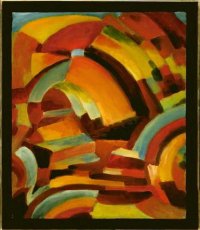

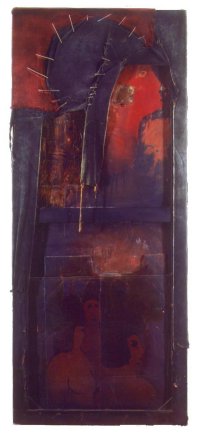

Now, back to San Francisco (forever, I thought). The Subterraneans is published after On The Road last year. I am taken by its spaces enclosing spaces as Jack's prose makes archway upon archway way into time. I see that he has done it with parentheses, and am reminded of the idea of Baroque as the link between Michelangelo and Einstein.

The idea of Baroque space as precursor of Einstein's equation was related to me by a young novelist during that great international flow of people following Word War II. He held the succession that arose from an unbroken chain of events beginning in Michelangelo's study of nudes and rocks recording the rout of bathing soldiers for the battle of Cascina standing as the first example in Western Art of abstraction. No one had before studied the human body so, the moment of fear in the short space between a river bath and the enemy. It is as if the muscles resonate almost in unison to sounds of the alarm tensing every muscle, making manifestation of those invisible waves the subject of the work. A pattern established within this idea is an unbroken chain of events in history: the work of art, newly risen, awakens a movement in a succeeding generation which generates an idea of space, the paintings being elevations of a new plan, so to speak, which works its way into the consciousness of those artisans of space, the architects. The buildings that result are erected over the span of a century (or more), so that succeeding generations passing through them are integrating the influence of the spatial idea into musculature, and thereby cerebellum, working its way to consciousness where it exerts cultural pressure on a next generation, refining it to philosophical proposition which asks then for codification mathematically and expresses in pure form, the view of the physical world embodied in the idea.

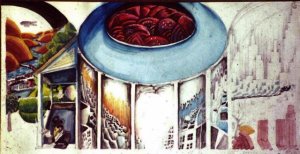

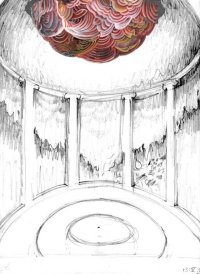

The example given is the ideal plan of a baroque building: a round room evenly punctuated alternately by arched openings and windows, mirrors between them. The arches open on two more arches and the mirrored space between them. Opposite the arch, a mirrored wall reflecting the view revealed, of an opening on two arches and a mirror reflecting a mirror reflecting the reflection. This is repeated around the room, as well as through the outer arches, themselves revealing more arches.

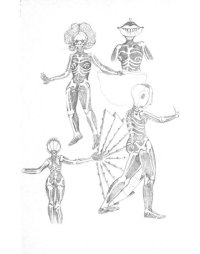

Later, as I worked in the theatre, my mind wrestled with the complexities of a world of pretense, to concretize words and the very real actions of man they signified. When part after part of the idea is enacted, each by its own actor, the great action of the play is revealed by the sum of them all. Subsequently, this great action postulates a great actor known as the 'double', ideally, of the audience, itself, and at its best, a single entity arising from the energy generated by good acting. But to the theatre worker, who must analyze what he is doing, and especially a scenic designer who is making the space within which the action occurs, it is a short step to realize that if the accumulated actions of the dramatis personae erect a double, a great actor of the play's action, then the stage before the eyes of the audience opens onto the interior of that actor's body.

From what organ of the body does the action of the play arise? The heart? The mind? The skin? (From inside, of course, as a space, a room, painted and penetrated). Not picturing such a space, but rather, relying on the the human mind's ability to connect the dots.

It was this epiphany that bore out the assertion a painting or drawing functions effectively on society as a plan of the future by inspiring other artists and then artisans to make a communal idea that forms a space describing the space our bodies enclose, our feeling and then knowledge, described in new ways by future generations.

The sounds of my friends' writings carve ideas in my ear.

While reading Book One of Virginia Woolfe’s To The Lighthouse, when the train of Mrs. Ramsey’s thought finally flows to Lily Briscoe, after having compared that houseguest painter with a famous mediocrity and his colony of imitators across the island, I am struck in the gut by some idea I can’t identify. The artist wanted to paint, not from fashion, but from some deep place in herself. I had been struck by the image of an abyss that seemed to occupy her center. She is roused from this meditation by the work on her easel which pictures the scene with people through whose thoughts we've just travelled. I misread (or rather visualized) Mrs. Woolfe's line as describing descent into a deep well, of 'tunneling' down into herself. I was transfixed by the sensation in my own body, of the experience she was having on the page. I was unable to leave the next page turned. Again and again, I returned that page to read the line again. I was an altar boy at a crisis of understanding.

As I looked, from where I lay reading, at a dozen or so canvasses leaning around the room, some of them freshly prepared and therefore blank, I could get no material handle on them. My mind couldn't grasp any memory of the feel of the scratchy, sometimes furry bare linen canvas to my skin, of any of the smooth grounds that were visible. Earlier, with Neal, I'd seen Rimbaud and Verlaine standing in their lithographed black London clothes, tiny and together, before my canvasses rising as skyscrapers before them where they studied them, then stepped over the wide gutter between floorboards for another view. I wondered, then, what lay 'behind' paintings, behind Art. I asked every painter I knew, every sculptor, composer, poet. No one knew what I was talking about. I was making one of those questions one gets asked out of nowhere, as by a stranger, without a context.

Philip Whalen, in a letter from Oregon, answered my plea for him to tell me what was happening,

"...it is a classical vision of death...an interruption of Creation...-a vision of...the idea of the words, "Never", "Impossible", "can not"-- & the idea is desolating & terrible because we so firmly suppose & enact & ARE the opposite of all this."

And indeed, I now know it is that search down into the void of being that brings forth a new existence for humankind. This search is that of each individual finding his own evolutionary path, some of us conscious of our path and some of us putting out notice that such growth is possible and actually happening on earth.

Jesse Sharp, when he spoke, spoke suddenly out of his dark fuming silences like a mad oracle, ideas coming in spurts followed by parenthetic remarks. Unlike Kerouac's parentheses, which make archway upon archway into unmeasured spaces of other times and places, Jesse would make a title of a line he'd just spoken by sub-titling it with an aside to himself, a generous offering to his hearer of another way to think the thought, but this time, with a new stress! This unique diction was recorded by John Wieners in "A Poem for Early Risers", in lines perpendicular to the main body of the text. Oh, how I wish I could hear, again, Wiener's unique Boston voice doing Jesse's (nearly) inimitable rhythm.

Jesse, once a coal-miner, then painter, adventurer, was half-Apache, an impassioned double of the part Peruvian Gaugin, would come mornings to my attic studio in the flat I shared with him, his wife and child, sit on my bed beside me and reveal his views on Art, who he was.

"Why do I paint?"

"I paint so I don't die like a cockroach."

"If the public doesn't hate my work, I look to see what's the matter with it".

"Painting has given me back my life; I can see better what happened in the quarrel with my wife that day on Disappoint ment Rock". "Disappointment Rock" was the name of a painting that hung in my studio.

In those long, slow steps across the wide threshold of waking from my sleep, to be told, as I was one morning,

"As I see it, the Universe is one huge painting. The job of the Painter is, in each painting, to sweep aside invisibility".

I was instantly awake, with a new, huge vision of the dimensions of art in space and time and how knowledge in the Cosmos was taking its course in and out of works of art.

"An Artist most nevair be in love; t'eez too hard on the nairves. You know, zee arteestic imagination "

-Georges de Batz

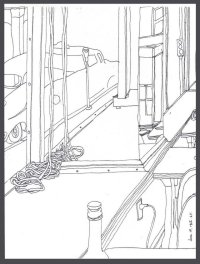

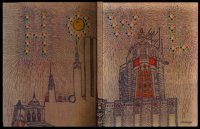

Herbert Blau had waited four years to use me as a stage designer. He told me on the phone at the picture framer's where I was then working, that he was preparing Endgame by Samuel Beckett. Get a copy and tell him what I thought of the play; would I be interested to design it. Of course, I jumped at the opportunity. I loved the play, seeing it at first from the perspective of my Jesuit education which Sam Beckett would soon help me get over. The inner workings of my mind were easily adaptable to the conceptual part of theatrical design, as was my inclination to construct visions in some kind of carpentry shop in my head. Herb and I collaborated well, our interests in literature corresponding and intelligent and we developed a close collaborative spirit that worked its way out into other parts of the theatre world.

ENDGAME

by Samuel Beckett

Encore Theater, San Francisco

1959

|

||

|

|

|

|

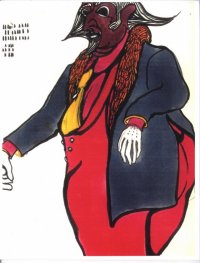

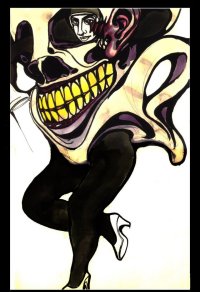

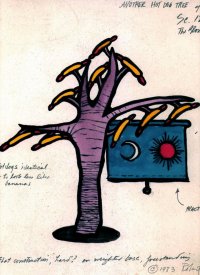

Dave Haselwood hatches the Mad Monster Poetry Reading to raise money for his Auerhahn Press. I'm to make assemblages that can be carried in a parade. They are to decorate the upstairs balcony at Garibaldi Hall on Broadway where On-Broadway Theater is now. The late, beautiful Ima Mahin did lighting. Kenneth Tynan taped it for BBC. Most of the poets did a wonderfully warm and spontaneous non-academic paper-rattliers' reading. A couple wannabe stars demanded solos, one asking, from the stage, for the lighting to be changed.

Philip Lamantia comes home to a glove nailed to his door. It is accompanied by a note challenging him on Sunday, to a Poetry Duel at Leo Krickorian's Enigma. I make him twelve-inch kathurni and a wide black cape that reaches the ground. He wears a huge solar deity mask, silver with serpent rays and a vellum mouth that magnified his voice. We approached, Mad Monster Poetry reading assemblages and banners aloft, on foot around a white convertible where Philip sat atop the back seatback, an straggly procession becoming electrifyingly ikonic as Philip dismounts, enters the cafe, pulls A Touch of the Marvelous from his priestly sleeve and reads his first recorded poem.

The difficulty for him, had been, how to respond to such a challenge from an upstart. Surely, he was not about to sit and trade the recitation of poems with a less serious artist than himself. But, like all straights, he could never ignore any challenge however unpoetic it may be.

Lady Day dies. At long last, we are permitted by the Censors of 1930 to 1960 ("too sad to be on the radio. It made people kill themselves"), to hear her sing on the radio, Strange Fruit.

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

As a descendant of O'Donellon bards, I knew somewhere deep in my cells, the power of poetry, how battles are won and lost at the arc of a line, how ideas burrow and shake the earth to rout an army. Little did I know how its power would alter history during my lifetime. How we've been gifted with the incarnation of Allen Ginsberg to our twentieth century.

Philip Lamantia and his companion Mimi Margaux are on Columbus Avenue walking, like me, in a beautiful sunny summer Sunday afternoon flan. We join up and move across Russian Hill to my flat on outer Washington Street. The air of the day was deep as poetry on the lungs, infused with the pleasure all such walks had on quiet windless days, so rare to San Francisco. We spend an afternoon of brightenings and an evening of illuminations. Philip writes part one of Blue Grace. This is the first time I smell Patchouli.

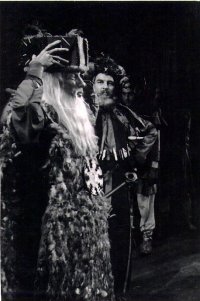

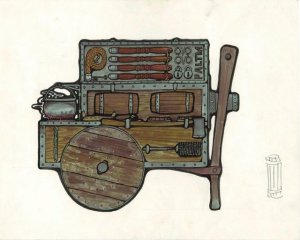

That fall began pre-production work on Shakespeare's King Lear. Conception continued into January, with early construction beginning in February for an April opening of the biggest show Actors Workshop had yet done. Somewhere, in a copy of the play that to this day I can't find, was "Place: Prehistoric Britain". Reality on stage is made from the same found objects as those used to make assemblage. Such objects, from whose traded meaning reality is made onstage, became the center of what interested me at the time: one thing masquerading as another. Sometimes the real thing pretending to be faking itself, with very hip actors inside it all, animating its richness and occasionally, revealing the mask to brighten blood flow in the audience brain. Western narrative theatre, unfolds events with words, spoken by people whose actions are given subtler meaning by their detailiing; an actor's use of an object gives it a meaning by assigning it a name based on its use in the action. This meaning lasts for the duration of the play. A regular rectangular solid is called 'cube'; an irregular cube is a 'rock'. The audience eye perceives only the two designations. What is the line drawn between 'cube' and 'rock'? The line of demarcation between the actual object and its accepted being onstage is in that summation of all the actors' actions, The Action of the play, mirror of that summation of all the folks watching, The Audience. Audiences subtitle the stage pictures before them. Indian dancers convert vast landscapes to stage settings with the turn of a finger as an outdoor Greek theater frames a landscape for actors to enter from great distances. Whatever the universe established onstage in the opening minutes, an audience enters that reality with its collective mind. It influences all interpretive decisions. The play's basis in the material world is established in that opening moment by the work of the viewer's mind to establish understanding of Where he is. There are poetic and amusing realities to this phenomenon, such as found objects peeking out around their resemblance to something else.

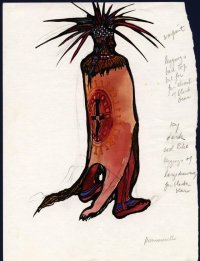

King Lear was put together from Prehistoric looking leftovers: hides, bones, tusks, feathers to create fearsome appearance, to display massive armed power in single personages by their costume. Abstracting the process of combining found objects into wearables, it was possible to make a setting out of rags put together by the same method, a unit set able to become architectural confines or large and open vistas, and with smaller details backing smaller scenes of action with pictorial interest. Herb, directed the actors blocking in architectural patterns which suggested buildings, colonnades, hillocks, so that actors became solely instrumental to belief in a staged reality.

KING LEAR

by William Shakespeare

Marines Memorial Theater

San Francisco, 1961

|

||

|

|

|

This process was so rich with possibility, it demanded exploration of its own method, beyond service to another artist, great as Shakespeare is. I made more assembled works, most of them larger because Leo had given over a balcony studio at the Enigma for me to use to make him a show. The result was 'The Black Art of Robert La Vigne', an exhibition of collage and assemblage.

|

|

|

|

||

|

Philip Whalen's recipe for frugal artist shopping:

Don't shop hungry.

Make a List.

Never shop high.

Don't buy anything that's not on the List.

I leave Sterling's, on Sonoma Mountain Road at dawn for SF, then SF International for a plane at 9AM. I am moving to New York. I arrive in the dark of a March afternoon and reach Allen's at Avenue 'C' and Fifth Street in the Lower East Side at six. It is the first stroke of what I come to learn is called 'culture shock'. We go to see Frank O'Hara's The General Coming and Going, but it's sold out. We join up with him at the box office and walk to Washington Square, the park just closed to Fifth Avenue traffic. The Washington Arch is lipstick graffittied behind O'Hara's pleasant face. The ground glitters from what looks to be broken glass.

At midnight, Allen and Peter take me to Times Square. Allen teaches me how to read the subway names and destinations, how to use the subway map, what to hold onto when passing between cars. We go to arcades, are hassled by hostile sailors, protected from them by police.

The first dealer I 'see' is Lee Nordness who had bought 'White' from Batman years before. He directs me up Madison Avenue to Fischbach where Steve Pepper offers to introduce me (I'm carrying art under my arm) to his friend who's opening a new space nearby.

His friend is the dazzlingly beautiful Paula Johnson (now called Cooper) in her first husband's elegantly appointed (from her knowledgeable hand) town house, a little gallery being built in the back of the ground floor. I can tell she is a lover of paintings. She buys a work or two and asks me to show with her.

Homesick for Sonoma Mountain and my friends in San Francisco, I come 'home' from New York. Then, kicked off the mountain, I sublet a studio in the Mission District. Rock and Roll has entered a phase much like the wonderful Grange dances of my childhood, dancing all night, children, babies on blankets on the floor. A new America is being revealed. Or rediscovered. Until it became apparent to the impresario that he could make more money from two sit down concerts a night. The first time I'd seen Americans lined up like cattle since the soup lines of the great depression, was when he took over the Village theater on Second Avenue to be the Fillmore East.

As usual, San Francisco has no money for a 'de-generate' artist's paintings. Back to work in theatre.

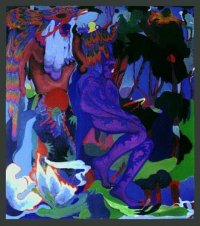

f all the people in the world to notify me of Bob Thompson's death in Rome, it's my landlord, fulfilling that strange feeling that comes from an Angel of Death (though this one not angelic looking) in a letter from Provincetown. It is a blow to me like a death in my own family. Young as Bob was at 29, and vital as a tornado, black and beautiful, his death seemed the expected next act of his drama. But unplanned. His death left a hole I my life that has never been filled. My own body then was turning thirty-eight (how very many are the poets who die at thirty-nine, I thought, and me slowing, tiring for the first time in my life at night from perpetual dancing in the newly unfolding rock scene of San Francisco.

Back in New York that fall, the central circle of Bob's friends gather at his widow Carol's new loft for her birthday. Seated at a round table, more as at a wake than a party, it was the first time we'd all been together since his death. A silence descended on the table like an invisible huge bundle that unwrapped itself, blanketing all the guests. Was Jay Milder the first to rise and make his farewells to Carol? Were did Red and Mimi there? When did Paula leave? In no time at all, it was over, and that old gang never gathered again until the opening night of Bob's show at the Whitney in 1998.

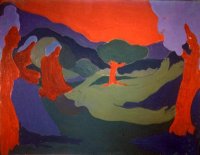

A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM

1966 Marines Memorial Theater, San Francisco, California

1967 Theatre de Lys New York

I get Jack Smith cast in A Midsummer Night's Dream. He is to be Snug, the joiner. He is so artful he misses all his cues 'preparing'. The Director explodes, running down an aisle screaming all the way to the orchestra pit, where he says,

"You're fired!"

(his favorite line) and turns, walking back up the aisle toward his desk. Jack leaps from the stage, runs up the aisle behind him and kicks him in the seat of his pants and leaves the theater.

Move: Desire Caught by the Tail

by Pablo Picasso

Bennington College,

Vermont 1967

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ENDICOTT AND THE RED CROSS

By Robert Lowell

American Place Theater, New York

1968

|

|

Julia Miles says I may be nominated for an Obie. I let the remark pass through my mind like a little piece of praise for my work. Months later, Ira and Rosalind make me buy new shoes. We are shooting Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda in New Jersey. I've gone to location late so I can attend Don McNeill's funeral at St. Marks in the Bowerie. Then, much is made of me attending the Obie awards ceremony. Seated with the Voice's minimal beer and chips celebration of Off Broadway Theatre, I'm surprised to hear John Hancock's name called for a Distinguished Direction Award for A Midsummer Night's Dream. I am surprised to hear Midsummer and Endicott called together and then my name.

After all the special preparations getting me there, I still hadn't gotten it, that I was up for an award, and then had gotten two of them on one day.

The last I saw Neal was a year or so ago at the end of 1967. We were going to live together in the little apartment I sublet from Richie Bright on East Second Street. He's just settling in when a girlfriend arrives and off he goes. Oh well. Then he's back for my move down the street into a big loft. He moves in with a duffel bag. We go out to Steve Paul's Scene with Hugh Romney. Tiny Tim is a new act there and after his last set, we go for a Cassady drive around New York to meet the dawn, our travels accompanied by Tiny Tim in the front seat, sounding like an old wind-up phonograph as he does his shtick with the toy guitar. Neal leaves for Mexico with the girlfriend and I never see him again.

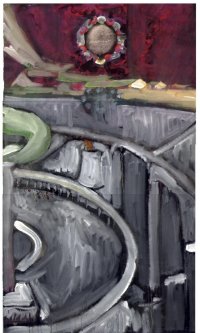

Trying to sleep this morning of January 15, 2001, my mind mulls over these events, seen anew, only by virtue of this assemblage of paintings and memories. The events of the fall of 1969, the painting I call Number One, 1970, the breakthrough in my work is being painted while Jack's blood comes up and he goes down, to death.

As I write this, during the hiatus of history taking place in Florida, I think of Tango Palace, and for its sea of index cards I see IBM punch cards. I see the play performed, in all its satin luxe, on discarded IBM cards flipped atop a pile of nuclear waste. I want to ask what play Ms. Fornes will write after the Bush putsch, but I think Tango Palace was already it in 1959, the time of Theatre of the Absurd. Will the Bushes get the trillion they missed when Clinton beat Dad. There goes the FDIC. Again!

One afternoon on Avenue 'A', in an autumn grayed not only by Neal's death (Jack's was yet to come within weeks) but a dismal New York summer, wet or overcast through all September, I passed another of those sidewalk carts left over from the days of Avenue 'C', this one with chandelier prisms on sale for twenty-five cents each. I invested in eight, and when I got home, hung them with fine gauge wire in my windows.

Next morning I awoke to the first truly sunny day for months, my aluminum foil walls covered with spectra from the prisms in the new morning sunlight. As I lay abed, facing the windows, I could see the sun itself in each, changing color as it moved through the various thicknesses of the crystal, and more fleetingly as the angle of the prism changed in the breeze. I returned to the shop and bought twenty more. Light filled that winter with color.

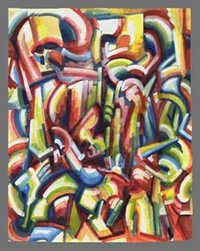

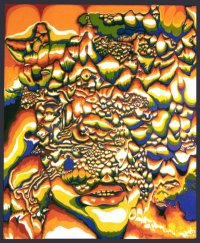

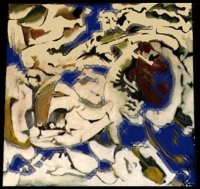

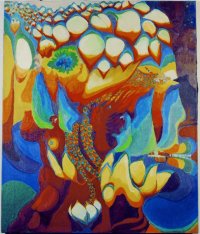

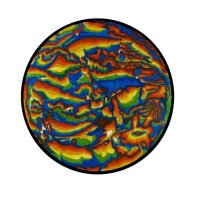

As I began work on the canvasses I'd prepared, I picked up where my work had left off in my last studio. As that first drawing unfolded from my hand, poetry began to grow outward, transforming the marks from a wadded rag I'd used staining the canvas, into mountain ranges, lotus petals, particularly the thousand-petalled one, and I realized I'd finally absorbed the experience of psychotropic drugs seven years before.

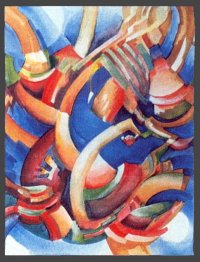

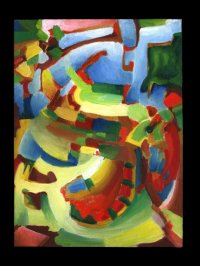

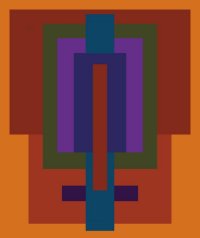

How to preserve the openness of a drawing when it is weighed down with saturated color? The prisms suggested a way into transparency, and as I began to work the drawing with the natural values of each hue of that palette, realized I could make a new drawing with each edge of a color as I applied it. Each shape became its own enclosed reference to an aspect of the material developing before my eyes. The paintings are not about the psychedelic experience so much as they record perceptions while using color to make painting, itself, real. Of finding a way to materialize that experience, and finally speak to the process of it, and matter's, construction.

I remembered being transparent, mesmerized by the shimmering of light being broken into color by irregular surfaces, particularly the scales of the two boa constrictors sharing the room with me on my first acid trip. Now, I could see how a large animal like man, as an aggregate of electro-magnetic fields, could easily and truly experience transparency. When the boson baggage of the electron soup is seen as it truly is, travelling through our 'selves', those invisible fields of force that form us, it pauses momentarily in that field of magnetism and then is pushed out again into diffuse invisibility. While in the field, the particles, clear as glass or water, are deformed, their collisions pressing one another into prismatic shapes, forms, diffracting light and thereby rendering the colors of light passing through them, visible to the eye. And Voila! The form of the field can be seen! We call it matter. Then I remembered feeling the air (or was it the ether) of the room pass through me, just as any magnetic field, or aggregate, must experience existence in Post-Einsteinian space and time, even as theoretical strings containing those six other 'rolled-up' dimensions must enclose define or delineate some space within the vibrations which characterize them.

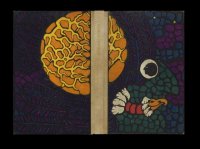

Far enough north of Los Angeles, at Cal Arts, the smog doesn't reach my bronchia and aggravate the asthma born of New York's terrible air. Napping, after a complete reading of Howl, the cement and aluminum vision of Ginsberg comes to me and I have the solution for a cover drawing to that special edition.

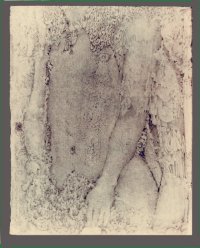

Cast in 1976 into homelessness by the workings of Hollywood, the small works begun last summer became the only possibility to continue working. Sitting in a kind friend's tiny apartment in Venice Beach, waking at dawn and working while coffee water boiled, I found the power of my eyesight increased hourly, the page brightening before my eyes, hour by hour and unbelievably, continued, even after noon as the light slowly fades, and beyond sunset when it would grow too dark to see, and I'd have to stop or turn on lights. How can it be that the reality of increasing morning light can be internalized to replace, as it seemed to be doing, the waning light of afternoon.

The use of frottage again, here, as a possibility of psychological exploration, was based in part on the legend of Pollock's works for his psychiatrist, I decided it was time to make a trip to my own interior. I decided the stained papers would allow me to do this, in a group of works large enough to accommodate such a journey and to cohere, along the way, in my perception. I would begin a drawing gradually so as not to introduce contrasts which would lead my eye away from discovery in faint differences between grays. As the work continued--now I was working on them from dawn till after dusk--I began at first glance to see the realized finished work already there to be developed by my pencil.

|

|

Not too far into this 'safari', it became apparent to me how dependent my life had been upon art; that possibly, I'd had no life outside Art. Definitely, I'd learned most of what I knew, before its walls. That I had found myself in Art. My being had needed growth Spokane does not allow, so that Art and mind had made a space for it to grow. Later, I realize how important it was that my seventh and eighth grade teacher, sister Dolores Marie had lifted me out of that world and planted me in more fertile territory. She was a great and dedicated teacher, still alive, so she must have been quite young then. Certainly a smart idealist who shared her knowledge by preparing her charges to learn from more advanced teachers.

Definitely, it was happening to me. Parts of figures from known or unremembered works would recombine themselves; a leaf I'd draw would remind me of one I'd noticed somewhere in someone else's hand somewhere in history and my mind would decide with a marvelous new freedom to draw each new leaf a new way, effectively (if intuitively) cataloging all the leaves I'd seen in the world and in Art. And learned to read my own hand 'writing'.

In 1978, as I turned fifty and my mother no doubt felt her death approaching, she wanted a last trip to St. Maries, the town in northern Idaho where her family had emigrated from New York; where she'd grown up, and where I'd been born those fifty years before in the house her father had built.

Alienation from one's roots definitely leaves one not 'up-on-the-news'. For the first time in my life, I saw the house by the river where my mother had grown up before grampa built the new house. When I drove to see the place of my birth, the green meadows, the pond issuing forth, the stream in its glen, what I saw was it filled in and paved over into a street of small town slums. The land had been sold off and there were dead autos in yards, trailers, the whole bundle of twentieth-century garbage. The shock was palpable in my chest. I was afraid, especially, of the hostile teens, (more dangerous than New York, where crime is business and therefore predictably less dangerous) laying about the porch rails by a window of the room where I was born.. They and the trash, dead cars, trailers in otherwise vacant lots, seemed the personification of a century from which the future had been removed; the hope and promise of American freedom rendered as trash as the waste accumulates, radioactive garbage piles up, knowledge of its lethal consequences unaddressed by politicians, industry, science. The future has been taken away from our people. The are no rewards or consequences.

During the nineteen-fifties newspaper front page fear maps, doing new Atom Bomb Scare to follow that dead Communist Scare, I dream of being in a white Directoire temple of Venus with San Francisco laid out beyond the columns. It was the view of City Hall from my studio at the Wentley. There is a whoof! The city is melting from a moment of bright light, down the walls of the temple, a painting failing to cling to its support. This old dream is recalled when I dream in 1978 that I am in my grandmother's garden by the house grampa built. On a porch in my mind which has transported from later in my life, to St. Maries, in the place where we would sit by gramma's garden in the house's shade. On the porch's wide rail, before one of its corner columns, a carved black bird in the austere Egyptian style. (I had not yet found my life in the motherless sculptor-architects, Horus and Moses.) Though black all over, it had a 'nun's hood', like many birds do, which seemed to scintillate with turquoise light, as if punched with holes like IBM cards behind which the light moved. I later found braille in the design of the lights. "Couldn't you see!" an aunt said in another dream. My eye was drawn to the sky at my left where a black dirigible very slowly moved. Its readerboard lights were also blue, the deep turquoise of the bird's hood, and were in cuneiform that I could read and understand. A movement draws my eye back to the porch. Leaning on an elbow in the in the foreground, is a crow, in a Brechtian tuxedo, lit cigar in hand, broad smile. The movement that draws my attention is a really pronounced wink. Twenty years of research fruitless, only recently to awake from a geriatric TV nap to see my crow teaching Dumbo to fly on a TV screen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last October, mother's stroke and the family shenanigans around it drop me into another Depression. I am reading Yeats' Autobiography, and am grateful to find I'm not the only soul to have been burned out of the theatre. In later years, I heard from Joe Martin the story he doesn't tell in his book, of counting money in the box office, not another soul in the Abbey Theater, when it came to him to ask himself,

"What am I, a Poet, doing here, counting money?"

While reading in him, I heard my name called out, "Bob" At first it sounded like some supernatural voice, the voice of God. Then I heard the timbre of my father's voice in it. Later, I heard my own voice in some electronic accidental feedback and realized my voice has the timbre of my father's.

More and more frequently, since 1955, I had been doing scattered reading in Proust. In the summer of 1980, I started on the first page and read Recherche from cover to cover. While undergoing a nervous breakdown. Yet.

My continued stay out of New York in the West of America can be excused, I tell myself, by Tennessee's ten years, outside sanity, on the 'West Coast'. Never before had I fully realized the meaning of 'nervous breakdown' with no recourse but to enter therapy. Wanting to cry in the canned goods brought to mind Alan Brody's character on the edge of tears choosing a can of corn in his novel, Coming To. My counselor urges me to take the First and Bell studio. I do. I sleep on hard floor of the lofted platform under the ceiling until I get a mattress. But I have space to work! The ideal image I had of myself then was in an apron standing at a table leaning over a painting or a frame, evenly lit by wonderful daylight windows. And now, here they are, tall, wide and overlooking Elliott Bay and Puget Sound.

When I was at the wall and paint began to move beneath my hand, I was in another world than Northern Europe's Guilds. Robert no longer existed. Like a phoenix, an unnamed self arose from the paint, invisible and as diffuse as an aroma, out of this world, crystallized and concentrated like the diffuse universe into the elements and their pigments.

I am! Yet what I am who cares, or knows?

My friends forsake me like a memory lost.

I am the self-consumer of my woes;

They rise and vanish, an oblivious host,

Shadows of life, whose very soul is lost,

And yet I am--I live--though I am toss'dInto the nothingness of scorn and noise,

Into the living sea of waking dream,

Where there is neither sense of life, nor joys,

But the huge shipwreck of my own esteem

And all that's dear. Even those I loved the best

Are strange--nay, they are stranger than the rest.I long for scenes where man has never trod--

For scenes where woman never smiled or wept--

there to abide with my Creator, God,

And sleep as I in childhood sweetly slept,

Full of high thoughts, unborn. So let me lie,--

The grass below; above, the vaulted sky.-John Clare

Written in Northhampton County Asylum

Having fallen asleep while lying on our new velvet sofa to study the bomb dream of 1935 that I'm working, I have a nightmare, obviously born of one of my New York muggings. Alone on a mile wide paved square, I see two armed baddies coming from the distance. There is no place to take refuge. In my paralysis, I unlock my fear-ridden chest with courage to cry out "Help?"....Louder perhaps?

"Help" Try again. "Hel..."

"Wake up Robert. You're dreaming" says my dear friend, Kevin. Ah, having a lover is having someone to wake me from nightmares.

My inclination is to think that the allure of parental love and mother, is to lure the infant into life, to eat and be a bigger animal, a bigger piece of food for the next higher species. And to look for eyes that look back so lovingly to find an Other to conspire in incarnation. In the case of man the animal, a strapping youth is able to work harder than a child. Or fight a war. An archival shot on TV last night of a bloodied skinny naked 18 year old (a big looking 15) on a stretcher in Vietnam. One sees who is the real fodder of war. No wonder the Tories don't like abortion.

Now, I'm well into painting every day by agreement with my shrink. It was here I discover that Pollock drew for his doctor because he was talk shy and the works he made and brought into his sessions made an opening to discuss matters working their way up into consciousness. It is called The Talking Cure.

In January, in New York review of books I encounter a review upon republication of a work by Ranier Maria-Rilke called Letters on Cezanne. The first letter describes a pomegranate and pear on his writing desk. The day the show of Rodin's Salome drawings opens, he has to get to it through rooms filled with Cezannes in that 1906 obituary retrospective. They were the first he had seen and he was so struck to discover of these paintings that he remained in Paris for the run of the show, visiting and writing of it in his daily letter home to his wife.

Rilke's most resonant passage to me was when the trees of a Paris street turned into a Cezanne painting he was walking through. From the first day's reading I was catapulted into blue to draw with it as I had thirty-five years earlier. Retro as these moments of discovery want to be and the unexpected places I was led by them, opened new insights into Cezanne. Seeing the surreal through him led me particularly to a new understanding of the small drawings from 1975 forward. I saw that the search into myself that had led me to understand that art is and has always been my mentor, showed me the influence there of Paul Cezanne, but not in the usual way. What I realized this decade later, is that the act of making a painting or drawing releases the surreal; that my earlier astonishment to see the powerful meaning in the negative spaces of my work and realize I was drawing things whose shapes surrounded a shape in the form of material my psyche wanted to come through in the work.

So. Also in Cezanne. I saw the great face of the sky mother overseeing the grand bathers; the Gauginesque idols in the quarry at Bibemus. I wasn't nuts. Dr. Reed, without comment, also saw them, if somewhat dismissively. Or is that couchside manner.

Can one trust these epiphanies? I remember the transport of those moments. Earthshaking. But then I recall an exhibition I painted in one year, definitely not enough time for this 'slow study' to make twenty paintings. Frequent ecstatic moments that proved to my later eye, to have led to a rather thin group of works. OK for perception, I guess, but not moments to work from. Yesterday. Today, they don't look so empty.

Yet, a matter of importance coming up in therapy would lead to intensely concise works made of common shapes with shared meanings. As when I got my first bicycle at twelve. Jerry Lieber knows,

"Is that all there is?"

Later that same year, I encountered Merleau-Ponty's beautiful essay, "Cezanne's Doubt". The first epiphany I had with that great philosopher, was to follow him through Madame Cezanne's account of her husband's pacing about the hillside for a long time before suddenly stopping and exclaiming,

"Aha. I've found my motif!"Something about the presentation of the scene and its idea (or its translation into English) made clear the meaning of Motif as motive in its sense as motivation. We had come up in America with the idea of motif as a piece of subject matter and the elements of its shape convenient to make a design. Here in Merleau-Ponty, we are back to the root, the stimulation of the artist's imagination by what he sees before him and its power to motivate him, as it did Papa Cezanne, to undertake the labor, resonating between his inner reality and that thing outside himself that interests him today. But I had gotten to see apples in the folds of Mt. St. Victoire before I read in Cezanne that he was seeing them too.

Reading further in Merleau-Ponty, his concept of Embodiment brilliantly captures the elusive workings of the brain as it locates itself in space by lines extended from its body's fingers, feet, eyes, nose, every protuberance continued to infinity, thereby releasing us from the prison of meat where we live. We erect a geometry of Space within our minds where metaphor is born. Such is the sense of relief we experience to see a great space visible out a window into which we can release our 'lines', stretch them. A replication of that space or a distant one conceived and alive to the eye before a painting on a windowless wall does not replace that experience. Rather, the emitted light from a painting's color impacts the retinal edge of the brain in a reversal of the process, inward, as in meditation. A good painting is a spectacular view of color itself. Color's wavelengths operate as metaphors for distance based on penetration of layers in the cones of the retina. Hence, abstraction's power. A window on Mind.

Glass, as in spectacles is a barrier to this direct experience of art. A sheet of glass works differently. By reflecting the viewer, it confuses the two experiences, mirroring and exercise in space, with each other. I see my paintings best with spectacles (appliances new to my geriatry) off. It is color, the direct penetration of the vitreous humor by photons and the retinal excitement shivering up the optic nerve to the brain that reminds us of reality. The nameable content of the work can be absorbed in seconds, details as afterthought when measured against the blast of actual colors raying into me, unblocked by a physical, no matter how transparent, barrier.

Merleau-Ponty's assembly of Cezanne material, surprisingly new to me then, illuminated where it wasn't confirming, much of what I'd gone through as an artist, and especially, in relation to Cezanne, the little drawings of the seventies, and works done since the Rilke Letters. Rilke had reawakened Cezanne in my heart and Merleau-Ponty affirmed and embellished my understanding of the way Cezanne's influence worked its way through so many painter's works into later history, growing there, I now know, even into the twenty-first century.

I get a drawing lesson from William S. Burroughs.

That hot summer between Ira's visit en route from Tokyo to New York in July and the Blackout in September which framed the event, I encountered a bumblebee in the living end of the studio. The bee was circling EZ Meditation, centered as bees are wont to do, on plants where they intend to get drunk from nectar. I am reminded of the story of a bird trying to eat a grape painted in a writer's memory of a great Hellenic Painter.

I watched as the bee zeroed in through the hot colors to Orient Yellow, the cute name for Cadmium Yellow Deep. Occasionally he would stray into white or a cooler yellow or, in another direction, into Cadmium Orange, always turning back to the hottest yellow, expecting to find it blooming with pollen, I supposed. That bee explored that color over almost half the painting before giving up and flying out my window.

Shall I tell of bees on my Marguerites in LA; they checked daily how soon the plant would bloom. And how, by the time one bee had reached the center of the corolla it was crawling from the weight of pollen like a street drunk, oblivious to my 8mm camera lens magnifying him from an inch away.

Six years in L.A and not another memorable moment.

I can recognize a shadow on the wall beside my bed up under the ceiling. It is a familiar shape I locate hanging before a window across thirty feet of studio from my sleep platform under the ceiling. It is moving up down and around on the wall beside my bed, part of the shadowy edge of darkness around a pale wash of light. I wonder where such light is moving outside my window. Some study (by my lines) reveals it is from the buoy off Alki Point, the southern tip of the crescent of Seattle around Elliott Bay. The buoy moves around with the waves beneath it, the rhythm of the pale light on my white wall in a slow-mo shimmy to a silent lyric about the weather out there on Puget Sound.

Suddenly, one night, I see a glowing glyph in the dark of my nighttime mind. A powerfully familiar feeling comes over me, almost indescribable beyond the sense of well-being that traces back to childhood innocence before the habit of piled disappointments has overtaken gullibility, as when, from therapy, I remembered with my whole being, the love my grandmother had lavished on me. This glowing figure was the first I remember building on a morning I remember as the first daytime call we paid on someone besides a neighbor or family. The smell of oatmeal mush permeated all the air of a Spokane Victorian kitchen large as that of Gough Street which arises in my mind as a twin floor plan of the room with table and doors. We are visiting my mother's oldest friend from childhood. She has, among other children, a boy a year older than me, a lifelong, if infrequently met, friend, now of late. This is the first person my age I've met and throughout my childhood, represented in my mind by a glowing glyph (made of morning highlights on his face?) which would come to mind whenever he entered my thoughts. Then, I remember, I had, for every person I knew, such a symbol that came to mind, was how I thought of the person. So familiar are these constructs of light and color, that to recall them, would be to remember the shape of one of my teeth: so familiar and belonging to no one but me, it is as indistinguishable from one memory of one day's (some 65.000 times I've brushed, so far) view of it in the mirror to the next memory or sighting or memory of a sighting.

"Don't you ever just sit in a chair, doing nothing?"

Dr. Reed is impatient, if amused, as he says it. One day though, I was relaxing, standing at a window, watching clouds over Elliott Bay and Puget Sound. In my mind, I was brushing the clouds over Alki Point and Bainbridge Island beyond, into the formations they were making in the windy upper atmosphere. As I stood in contemplation of the sky, unlocking my knees to ease the pain in my back, it became clear what I was doing and accounted for some of my distress. It had always pleased me, when looking at classical painters, to imagine the particulars of their non-verbal mindset as they made their hands push the brush sweeping white paint into wet blue sky as a wind would work clouds.

When I told Allen I hurt my back lifting Nude With Onions, impatient for an assistant's help, he says,

"Ah! Karma."

Here I am, I thought, doing it myself, without a brush in my hand, tiring my mind with imaginary work. Later, as I passed an open window at the rear of my studio, peripheral vision revealed a wooden factory palette leaning near the freight elevator across the roof from my studio kitchen. A swift refusal to look at its condition, lest my mind enter that work state I was trying to escape (to improve, lift, repair Aha! Repair. There's a hammer. There's a hammer in my head). To repair 'It'. Unable to resist, I look. Sure enough, one of the palette's slats is broken and I'm already hammering a new slat somewhere in my brain. Now, a new task before me, to work this habit out of my system.

Steve Chandler has made a typo in a card he printed from my journal. Actually, he's not caught the Yeat's reference in "Y tooker innisarms anmaaderis the long night over…" I think of it in the night clearing from a storm. I've lost another lover. I've lost my sweet birds. Surely someone can at least remember 'Lake isle of Innisfree'? Was that Yeats coming through in my line? It is four in the morning. I get up to find "Lake Isle of Innisfree". I open to Yeats' section in Oxford English Poets. The first poem is "Where My Books Go". I have never noticed this little poem before.

All the words that I utter,

And all the words that I write,

Must spread out their wings untiring,

And never rest in their flight,

Till they come where your sad, sad heart is,

And sing to you in the night,

Beyond where the waters are moving,

Storm-darken'd or starry bright.-William Butler Yeats

Where My Books Go

Twenty years earlier, I had discovered with drugs, the difference between a vision and having to construct the Imaginary in my mind from raw materials, as I would build a construct, and the gratuitous appearance before one's eye or mind's eye of a 'vision'. Is this a metaphor for something bigger, I asked. The householder? The Hermit?

PAINT: An Artist's Statement

The marvelous substances of which paint is made and used by an artist to reveal the structure of things, do so with the very materials of which the motif itself is made, carbon, iron, or hydrogen. Likewise these substances, here on a canvas, are illuminated by light created and released by the same substances consumed out there in the solar furnace. It is through the relation of the artist's interior life to image, an emergent biography of the unconscious that tests those excavations for authenticity. This process shows where paint handling is efficacious or fails to deliver. It is this activity which certifies in the artist's mind that the hand-arm-shoulder brain is in touch with a correct image of Reality. This is true on whatever scale it may exist; be it in the room, landscape, world, heavens or beyond the power of imagination to anticipate before the work was made and began to live before the eyes of others, to influence the future.

It is a search for the unknown, unseen and un-named that is usually supposed to belong to the conscious mind. However, now that we know the Self is seen by scientists as an artifact of the conversation in the bicameral brain, I feel safe saying the conscious mind itself is best represented by the left brain. This half is condemned to forever replay it's serial reality in language and in numbers. And when left is alone with the right brain, its questioning, nagging voice we call Self, ransacks the storehouse of feeling on the right for its sensuous experiences and sets about busily codifying them in left brain terms. Tired from that labor, it claims authorship of its appropriation.

The process of Ideogram containing Pictogram is the most interesting of all questions about early man. It contains within itself the results of dialog between the two hemispheres. The left assumes language is the only clear communication because it's the side that does the talking. Consequently, the left brain does not create anything that is free of the past. In its demand for the certainties of precedent, it is trapped in Time. Painters, manipulators of materials to delight the senses, discover heretofore unknown truths about the nature of our existence and environs, such as those flaws of coloration, the centuries old black holes which suck the viewers' attention away from the rest of the painting and into themselves.

To remove paint from service to Image alone is to free it from bondage to time. It is where I see my work directing itself, as if all the information about the world and myself has been seen and the motions of the universe on the surface of the canvas want only to be free of the small scale of the field whereon we live.-Robert La Vigne

Seattle, 1993

How surprising it always is to find myself producing a work, pertinent and useful to a project after months of studies and even finished drawings, while waiting to choose which to use. Then, in idle exercise, IT will come. I am stunned, each time, that this could be how it happens.

A curious property of the brain exhibited to me after open heart surgery, was its unavailability for the kind of intense concentration needed in extended work. It's full time occupation was directorship of my body's healing from the trauma of surgery. After ten or twenty minutes, during the first two months of recovery, interest in what my mind was occupied with doing, simply stopped. Later, I found I could work, with practice, on small and easy projects.

Clearly, this first-hand knowledge of a need for total access to the brain reveals a lot about the social trait of humanity, and how it's at loggerheads with the basic law of creation: big fish eats little fish. Now, scientists have gotten to watch atoms of tin on copper, perform as if alive and trailing bronze. An aside on Society: by big fish banding together, they get to eat all the little fish. From the standpoint of man's higher mind, how can there be a Great Mind as Creator, when the mind of Man is imprisoned in a brain that is only meat to another animal.

To the Viewer:

These photographs by me & drawings & watercolors by Robert La Vigne mark over four decades of friendship and artistic collaboration. Robert La Vigne was so to speak the `Court Painter' for the large group of poets gathered in mid Fifties during `San Francisco Poetry Renaissance' beat period. His work - large oils & drawings of Peter Orlovsky & John Wieners - occupies an honored corner of the Whitney Exhibition 'Beat Culture & the New America 1950-1965', presently installed at S.F.'s DeYoung Museum. La Vigne was painter among poets, and made sketches of Neal Cassady & his lady Natalie Jackson (hung here side by side with my photo of Natalie & Neal under the marquee--drawings of Philip Whalen, Poet, now Roshi Whalen of Hartford Street, S.F. Zen Center (who delivered a cache of La Vigne's drawings & watercolors left in his hands decades ago for this Gallery exhibit--of Gary Snyder; also portraits of Kerouac (cover illustration of J.K.'s Scripture of Golden Eternity), of Philip Lamantia. His orgy drawings of myself, Natalie J. & Peter Orlovsky can be found in my Collected & Selected Poems under the appropriate texts, as well as his illustrations of A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley (done for a poster) and Poster of Kral Majales reproduced in aforementioned volumes. Working with Auerhan avant guard S. F. Press & David Haselwood printer he designed the cover of Olsen's Human Universe & later a cover for my limited edition of Howl. He had made panoramic orgy scrolls-ink illustrations which encircled the audience at Berkeley's Little Theater March 1956 for the first complete reading of "Howl" & first recitation of "Sunflower Sutra" & "America." This exhibit, including 1996 drawings by La Vigne (#'s 29, 20 + 31, 32) for a cover of recent booklet of dreams to be printed in Spain, thus honors a long & deep art friendship."-Allen Ginsberg.

Can man find an existence independent of the meat we live within? Which wannabee Queen of England coined the 'Court Painter to the Beat Generation' number that Allen repeats.

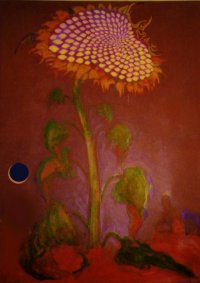

This is a study for a painting in memory of my late friend Allen Ginsberg, well-remembered by many for "Sunflower Sutra", a poem that addresses, before it happened to him, the subject of his surprise later, after the publication of Howl, that the book had reached small town America. The 'lone goof in town' learned from it, that he was not alone in the world, that there were other towns, and each had its own single outsider.

In the poem, he directly addresses us as he speaks to the dried stalk of a sunflower growing from an industrial garbage heap.

"--We're not our skin of grime, we're not our dread

bleak dusty imageless locomotive, we're all

beautiful golden sunflowers inside, we're bles-

sed by our own seed & golden hairy naked ac-

complishment-bodies growing into mad black

formal sunflowers in the sunset, spied on by our

eyes under the shadow of the mad locomotive

riverbank sunset Frisco hilly tincan evening sit-

down vision.Ed Sanders' account of his teen-age whoops of joy in a Kansas backyard, his newfound freedom after reading Howl is one of the best I've encountered. I think its in one of my favorite books, Tales of Beatnik Glory. (When do we get volume three, Ed?) This is a study for a memorial to Allen.

Painting is like a piano. Not furniture straddling a lot of carpet. More Piano-Forte, the instrument's sharp cut hard and soft plucked song in air. Some atoms gathered there on a wall, their colors waving chords that jiggle my cells in unison. Eye is warp-speed edge of Mind, the viscera itself waiting in the brain pan for a lid to pop open onto painted slabs flinging photons along the optic nerve in a direct line to the center of that gray organ.

November 25, 2000

Just today, looking for the passage on motif to get papa C's quotation right, I encounter a reiteration of my thoughts trying to write this, to explain my life. My note reads:

"Organization is contrary to the principal of discovery by determining the outcome, predicting the outcome". In my search of M-Ponty, for something else today, after weeks of fruitless search, I find the motif passage:

"His meditation would suddenly be consummated: 'I have found my motif',..."